Bologna’s First Big Twin

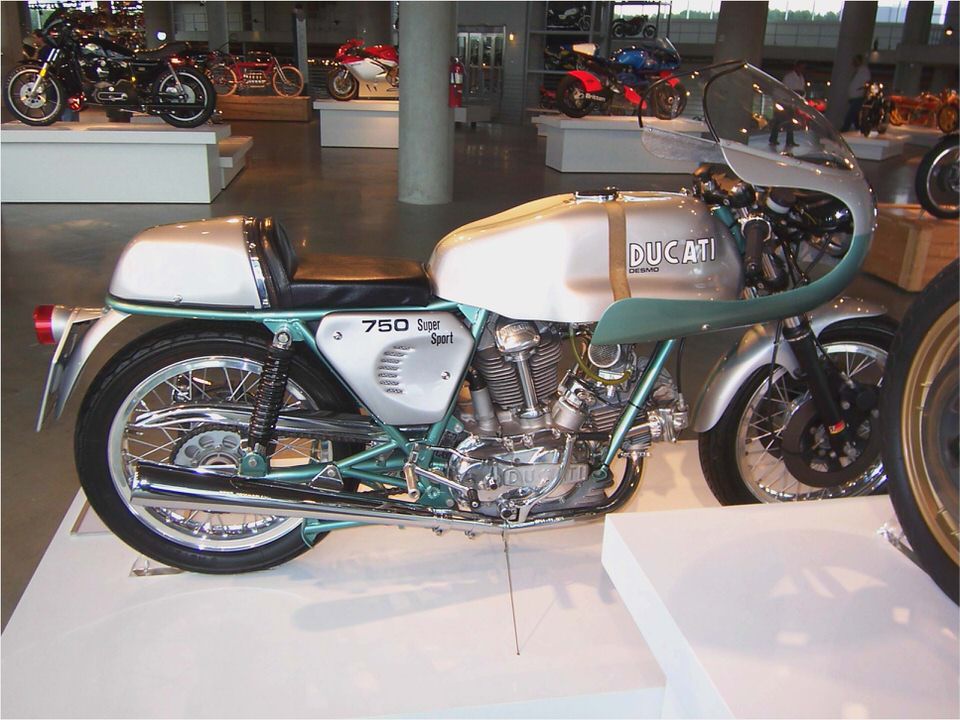

Silver metalflake paint is a sign of the times, and an indication that American trends influenced more than just the Ducati 750’s engine displacement in 1972.

Silver metalflake paint is a sign of the times, and an indication that American trends inf

With Ducati winning 14 world titles in the past 20 years, we tend to take its Superbike domination for granted. But before a certain afternoon 40 years ago, the Italian manufacturer had precisely zero big-bike credentials. Primarily a producer of small-displacement singles, Ducati at that time had nothing to take on the championship-winning fours built by MV Agusta or Honda, let alone the many twins and triples from established makes like Triumph, Norton, Moto Guzzi, Laverda and more.

Ducati was an outsider in the big-bike brotherhood.

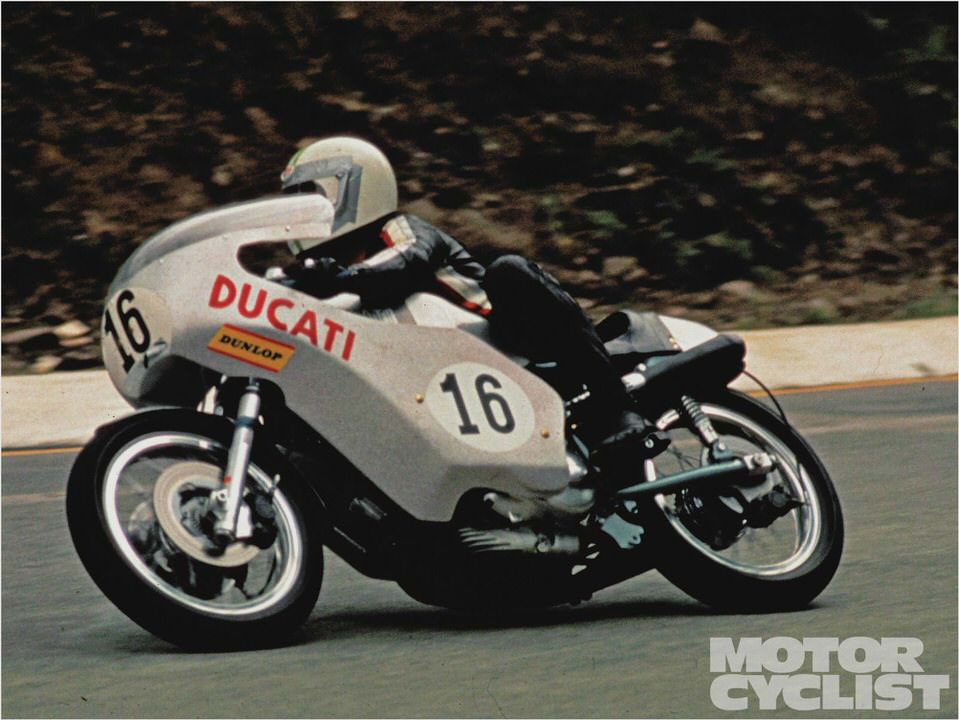

Paul Smart’s victory aboard the Ducati 750 SS at the 1972 Imola 200 changed everything. Inspired by the Daytona 200, this was the first important race held outside the USA for the new generation of Formula 750 Superbikes. When Smart and teammate Bruno Spaggiari finished 1-2 that day, not only did they establish Ducati as a proper big-bike manufacturer, they also set the wheels in motion for the formation of today’s World Superbike Championship.

Famed Ducati Ingegnere Fabio Taglioni’s first V-twins appeared in 1971, in two forms: a 500cc Grand Prix racer and the 750 GT streetbike. Taglioni created these by essentially doubling the Ducati single, locating a pair of bevel-drive, SOHC top ends on a shared crankcase. Several frame layouts were tested before Taglioni settled on Englishman Colin Seeley’s prototype design, consisting of a tubular-steel trellis employing the 90-degree V-twin as a semi-stressed member.

With the help of factory test rider Franco Farne, Taglioni created a special factory-racing 750 Super Sport (SS) to compete in the inaugural Imola 200. The engineer believed—rightfully—that a good result in this new racing format would make a big impression for Ducati’s new Superbikes. Taglioni’s goal was to build a racebike that could approach the 170-mph top speeds of the Japanese and British 750s, but with improved reliability and better handling.

Simple tachometer resembles a repurposed pressure gauge. Redline resides at 8500 rpm, several thousand below the other factories’ high-revving Multis.

Simple tachometer resembles a repurposed pressure gauge. Redline resides at 8500 rpm, seve

To the untrained eye, these factory racers looked remarkably like production 750s. The frames appeared stock, just fitted with racing suspension and a steering damper, and the front wheel sported a second disc brake. Bigger changes lurked inside the engine. The conventional valve springs were gone, replaced with a more precise and reliable desmodromic valvetrain from the racing singles.

Bigger, 40mm Dell’Orto “pumper” carbs and a new racing exhaust combined to produce 84 horsepower at the wheel.

Spaggiari was a veteran Italian racer with many international victories on Ducati singles. Smart was a less obvious choice. The British rider was racing factory Kawasakis in America at the time, and wasn’t contacted by Ducati until one week before the race, after Renzo Pasolini, Jarno Saarinen and Barry Sheene all turned down the opportunity.

Smart might have turned it down as well, if not for his wife Maggie—Barry Sheene’s sister, incidentally—accepting the offer in his absence.

“I’m not riding that bloody old thing,” was Paul’s first response when Maggie told him of the deal she struck, until a “family discussion” changed his mind.

Smart wasn’t immediately impressed with his first ride on the Ducati, at a Modena test track. “They didn’t need steering dampers, because with a 60-inch wheelbase they wouldn’t go ’round corners anyway,” he recalls. “They felt pretty awful to ride, and slow, too. There was loads of torque, but it seemed to fire every other lamp post.”

Appearances can be deceiving, though, and Smart was shocked when mechanics told him he had broken the lap record held by Giacomo Agostini’s works MV Agusta. “It hadn’t seemed I was going that quick, because the Ducati hardly seemed to be revving at all.”

So it was with confidence that Ducati arrived at “The Daytona of Europe,” where the 750 SS would debut before 70,000 rabid spectators. Imola’s fast, sweeping circuit suited the Ducatis particularly well, and even against works entries from nine different manufacturers, they were in a class of their own. Smart and Spaggiari qualified first and second, ahead of Agostini on the MV.

When it came time to race, Ago lead from the start and stayed out front for five laps. Smart knew the race was his to lose after overtaking Ago in Imola’s high-speed Tamburello curve. “Ago found the MV a handful there and would ease off quite a bit, whereas the Ducati would go through flat-out,” Smart remembers. “The fifth lap I kept it nailed open and swept effortlessly past him. It was a great demonstration of the Ducati’s handling, and after that it was obvious either Bruno or I would win.” It ended up being Smart, who pulled away on the last lap to claim victory by 4 seconds.

That day, April 23rd, 1972, was Smart’s 29th birthday, which made the win particularly satisfying. But the real birthday was Ducati’s. That day began a Superbike dynasty, the first of literally thousands of victories for the Bologna builder’s 90-degree desmo V-twins. MC

- Ducati Sports Classic GT1000 Review, Ducati Sports Classic GT1000 in India…

- 2012 Ducati Monster 1100 EVO Review – Ultimate MotorCycling

- Ducati Desmosedici brought to you by MadaboutMotorcycles

- Ducati 1199 Panigale S Senna Limited Edition showcased

- Ducati Superbike 1198 Price of india Features top speed Myyouthupdate.com