YAMAHA XS1-XS650-TX650

The origins of the Yamaha XS650 reach back to 1955 and now defunct Japanese manufacturer Hosk. Hosk made an impressive and fast 500cc twin modelled after the German manufacturers’ HOREX 500 seen below. After @ 10 years of producing the 500 twin, Hosk engineers designed a 650cc twin.

Hosk was then acquired by Showa Corporation, and in 1960 Yamaha bought Showa.

When the Yamaha XS 650 was unveiled in ’68 it had a very advanced design. The engine and gearbox were unit construction with the crankcase split horizontally for ease of assembly and maintenance where most (British) contemporaries in 1968 had a vertically split crankcase or pre-unit, with separate engine and gearbox.

Mid-’77 the front forks had a major redesign. Fork tube diameter increased from 34 to 35 mm and internals were changed (although this also holds true for various years of the same tube size).

The entire fork assembly with triple tree will swap either way but fork parts are not interchangeable. Also the brake caliper changed from a 48 mm dual piston cast iron design for the 34 mm fork to a 40 mm aluminum single piston floating caliper for the 35 mm forks. The brake caliper mounting lugs on the fork sliders are of different spacing for the 34 mm and 35 mm forks so the calipers can’t be swapped.

The XS 650 was produced until 1985. In the United States, the last model year was 1983 with Canada, Europe and other markets continuing into 1984 and 1985. However, many US models were left over due to overproduction and an economic recession and brand new 1982 and 1983 models could still be purchased in 1987 at some dealerships.

Carburetion

Yamaha XS650 models pre-1980 use the twin 38 mm constant velocity Mikuni carburetors that can be tuned by moving the needle clip position, or by replacing jets.

Ignition

Up to ’79 all models used points ignition. Two sets of points are located on the upper left of the cylinder head. On the right side cylinder head, an advance mechanism is located. And advance mechanism is used to retard the timing for easy starting and smooth idle.

Post-1979 models use electronic ignition systems, and although earlier points units were generally reliable, well, electronic is definitely the way to go!

Performance based on results obtained from the 1979 XS650; Standing-start quarter= 13.86 sec at 96.05 mph Average gas millage @51 mpg

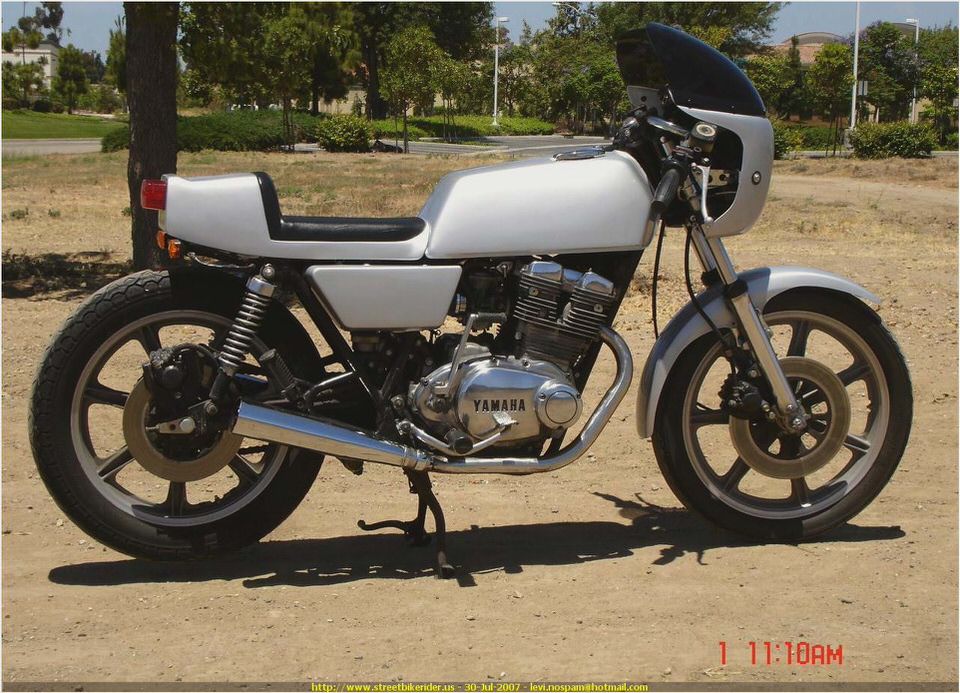

These days, the Yamaha XS650 is a very popular basis for modifications and specials. From cafe racers, street-trackers, flat-trackers, hyper-motards and whatever the imagination can conjure, the Yamaha 650 will be the most popular bike for classic Japanese motorcycle specials builders for some time to come.

Yamaha XS650 Special

overpowering your yamaha XS650

wise words from Craig Weeks at 650Performance.com

650Performance.com is the go-to spot if you want to build big power into your Yamaha XS650 motor safely. Says Craig.

Now that people are putting their modified engines with the CNC’d heads on the street and race track I’m becoming a bit uncomfortable with what I’m hearing about how radical some of their modifications are.

The XS650 cases, clutch and transmission were designed for an engine that would make around 42 rear wheel horsepower (RWHP). When Yamaha was in the middle of the dirt track wars in the ’70s, the engines built for Kenny Roberts and others on the factory team (as well as the best privateer engines) were putting out right around 70 RWHP and reliability wasn’t generally a problem.

The best engines built by Bud Askland, Harry Lillie and others were inspected after every race but would typically last a half season or more before any major replacements were required. Compared to the BSAs, Triumphs and Nortons this was a real luxury.

When Harley took the next step in XR750 power Yamaha responded by pushing the XS650 power envelope even further. With Tim Witham in charge of development the XS reached the 75 RWHP threshold with stock head castings. While the bikes were rockets, things began going wrong.

Broken transmissions, cases and connecting rods were the worst, but clutches and valve trains were breaking too.

You probably know the story about how Yamaha’s response to this was the fabled OU-72. What some people have forgotten is that the OU-72 didn’t just have a sophisticated revised XS650 cylinder head with previously untouchable flow numbers, it was also accompanied by all the reliability tricks Tim Witham had learned – strengthened cases, Webster transmissions, thickened and deeper clutch baskets, alloy rods and a host of other upgrades.

The first XS engine that Harry built for me was exceptionally powerful. It was a full AMA-spec build and was the strongest XS engine I’ve ever run.

After about a half year of racing it at Sears Point with AFM another racer was looking at the bike and pointed out a small crack in the cases, right in front of the cylinders around the oil up tube fitting. When Harry dismantled the engine the cracking was found to have extended all the way down into the cases and around the crankshaft webbing.

We tossed those cases and took the edge off the rebuild by lowering the compression a little bit, richening the Lectrons a little bit, advancing the cam a little bit for more midrange, etc. and it dyno’d out at 71 RWHP. Perfect. Since then I’ve always run my engines in a state of tune that gives them 69 – 72 RWHP and I’ve never had a catastrophic failure.

The point of this message is that the stronger cases, clutch baskets, etc. aren’t available today. They are either worn out, broken or lost. And the specific lessons learned from piles of broken parts about how to modify your engine to live happily at 75 RWHP are long forgotten by the men who developed them.

If you have a good OU-72 head, or you are one of the people who recently received one of the new CNC’d heads (or you have any head that really flows well), you have the potential to reach 75 RWHP.

For the reasons above, I caution you to resist the temptation to raise the compression a bit higher than discussed in my XS engine modification guide (see 650performance.com if you don’t know about this), or tune it a bit sharper, or bias the power curve to toward the top end, etc.

If you have a solid 70+/- RWHP or less your bike will run really hard on the street or race track and (if it’s put together correctly) will be reliable.

Remember: 69 – 72 RWHP = reliable. 75+ RWHP = expensive things break.

The images above and to the left here are the work of Gordon Calder, an obviously talented photographer who has created many motorcycle related works of art by concentrating on light/shadow, detail and contrast.

Mr. Calder obviously has a keen eye for dramatic images where most of us only see the big picture, and this, among other talents, enables Calder to tease out the art in industrial technology.

1974 Cycle Guide XT650 review

This is an edited version of the review, if you can believe it!

This year’s TX650 gets an A on its name. and a C+ on its report card.

Multi-cylinder super-bikes have evolved into machines that can handle almost as well as twin cylinder bikes, even though the multis are wider, heavier, and have a higher center of gravity. Even so, heated debates still take place all around the world as to which design, twin or multi, is the best.

All the pros and cons of multis have undoubtedly been considered by Yamaha, but they have stuck to their twin-cylinder guns. Instead of taking a big jump into a three- or four-cylinder touring machine, they have elected to refine their present line of twins.

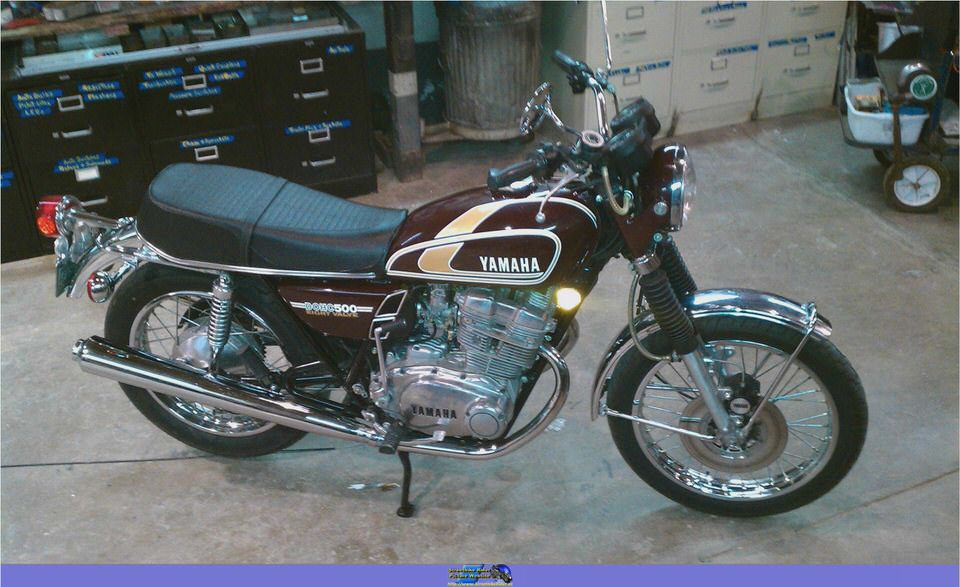

Since its inception in 1970, the Yamaha TX650 twin has been battling for positive recognition. It has sold well and has been one of Yamaha’s most reliable models. But the original XS-1 had some unusual handling quirks that have been part of the bike since the beginning.

Some riders never let the 650’s wiggling and wobbling bother them; but others, whose level of tolerance was much lower, confessed to never feeling quite confident aboard a 650 Yammie.

This year’s 650, called the TX650A, has gone through some frame and suspension changes that are major enough to qualify the chassis as being all-new. Yamaha made these changes in an effort to rid the 650 of its unusual handling traits, which, in turn, would clear up any blemishes on the bike’s reputation. Since the primary advantage of a twin is its supposedly better inherent handling, the TX650 would not be considered a true success until it overcame its inhibited road behavior.

THE BIKE: Our test bike, the Yamaha TX650A, uses the same basic powerplant as last year’s TX650. The narrow, very tall engine retains its slightly oversquare 75mm bore and 74mm stroke, which give it a total displacement of 653.8cc. The compression ratio has been lowered to 8.4:1.

Straight-cut primary gears transmit power from the 360-degree crankshaft to the large, multi-plate wet clutch and five speed gearbox. The gear ratios are close together and evenly spaced, so no big rpm drops occur between shifts. A single-row chain drives the overhead camshaft, and dual 30.6mm Mikuni-Solex constant-velocity carburetors supply the gas mixture to the engine. A two-piece airbox mounts under the front portion of the seat and houses a pair of washable, oiled-foam elements.

Another piece of foam is placed behind each element to filter out the big pieces. An easy 90-degree turn of the wing-nut knob on either side panel gains access to the filters.

The Yamaha uses a conventional battery/coil ignition system. Dual breaker points mount at the left end of the over-head cam, and a massive AC generator hangs on the left end of the crank.

A panel just in front of the handlebars holds the speedometer (which reads nearly five mph fast at 30 and 60), tachometer, ignition switch and idiot lights.

The 650 uses a double downtube frame that has a single, large diameter backbone. Heavy bracing and gusseting have been added to this year’s frame to give it added strength and permit less frame hexing.

The bike has a sidestand on the left and a centerstand; it doesn’t take much effort to get it up on the centerstand, but you must lean the machine way over to the right of center to get the sidestand down. If you have short legs, or if you’re standing on the left, the bike can easily fall over on the right side while you’re trying to get the sidestand down.

The TX650A uses alloy rims at both ends, with a 3.50 x 19 Yokohama ribbed tire up front, and a 4.00 x 18 Yokohama universal on the rear. A double-action hydraulic disc brake stops the front wheel, and a single-leading shoe drum brake gives the rear wheel its stopping power. The front forks allow 4.9 inches of wheel travel and the five-way adjustable rear shocks permit 2.8 inches of rear wheel travel.

Chrome fenders, shocks, exhaust pipes, and chain guard, contrasting with the matte black finish of the handlebar switches and instrument panel, give the TX650A a neat, modern appearance. The four-gallon (last year’s was 3.7 gallon) Cinnamon Brown gas tank, side panels, and headlight also blend in nicely, but the frame detracts from the bike’s otherwise clean overall appearance. It has gussets supporting gussets and frame tubes bracing frame tubes, all held in place by thick, heavy welds.

Other than that, the machine’s workmanship is well above par, and all the pieces fit together nicely.

ENGINE AND GEARBOX: The TX650A has a wide range of usable power which begins just above idle and lasts to engine redline at 7500 rpm. It builds power smoothly and steadily and there is never a spot in the powerband where the engine comes on all at once. There aren’t any flat spots throughout the range either.

The bike accelerates best between 4000 and 7500 rpm; maximum horsepower is at 7000 rpm, and the torque peaks at 6000.

This steady pull gives you the feeling that the bike isn’t exceptionally fast. We were really surprised when it turned a 14.42-second quarter mile with a terminal speed of 92.2 mph. These figures are close to those of some superbikes we’ve tested.

To start the engine when it’s cold, push down the enrichener lever on the left carb, turn the key on, and push the starter button. After a few seconds of cranking, the engine comes to life. Let it idle for 30 seconds or so, lift the enrichener lever, and you’re ready to take off. When the engine is warm, the procedure is the same, except you don’t need the enrichener at all.

There is also a kickstart system in case of a failure in the electric start system, but it takes a healthy prod to turn the engine over. Last year the TX650 had a small lever on the handlebars which was hooked to the starter motor and also operated an exhaust valve lifter (which acted like a compression release). Pulling this lever would activate the starter and lifter simultaneously.

But the starter cranked the engine over so violently that it often jerked the crankshaft flywheels out of alignment. Once this happened, the already-heavy engine vibrations would become heavier.

The TX650A doesn’t have the valve lifter this year, and it uses a starter motor that transmits less torque to the crankshaft so the crank stays in alignment. But it sometimes takes three or four pushes of the starter button before the starter gears engage. The spring in the Bendix starting unit is too strong and won’t always allow the starter gears to mesh.

The resultant clunking and whirring sounds are terrible.

For the smoothest starts, we found that revving the engine to 1500 rpm and letting the lever out very slowly was the easiest way and required a minimum amount of clutch slipping. If the engine rpm was, below this point, the bike would chug and surge and sometimes stall when the clutch was engaged. If the revs were above 1500, we had to hold the clutch lever within this three-quarter inch engagement area until the bike was moving about 10 to 12 mph.

Above 10 mph the engine works well; it never wants to chug or bog out unless the revs drop down below 1500. There is plenty of overlap between the gear ratios, so the engine rpm doesn’t drop much between shifts. When you’re in the hefty part of the powerband, it’s easy to stay there.

The TX650A has enough power to cruise the freeways and open roads easily. There is enough reserve power in top gear to let you move easily with the flow of traffic. For the quickest acceleration to pass slower vehicles you have to downshift once or twice to get the revs above 4000; but you can also pass comfortably in top gear.

At freeway speeds of 55 mph the engine is only turning an easy 3700 rpm in fifth gear or 4200 in fourth.

If you like to play racer on winding roads, you don’t have to shift a lot to keep the engine above four grand. Third gear lets you run close to 80 mph without over revving the engine, and in fourth you can go over 95 mph.

Yamaha found it necessary to redesign the cylinder head cover for more efficient top-end oiling. However, improperly designed baffles in the cover let oil seep out the breather when the engine is running; and when it’s stopped, oil that accumulates in the breather hose falls to the ground.

We liked the gear ratios and overall gearbox operation very much. The shift lever travel is short, and the shifting was always smooth and positive. When the bike was new, we experienced some difficulty finding neutral from first gear.

About 50 percent of the time we would miss neutral and end up in second. But shifting from second into neutral was always a no miss proposition. After the gearbox limbered up, this problem ceased and we never again missed a shift.

The clutch took some punishment, but it always acted like it should: It never chattered or grabbed.

HANDLING: The frame has undergone some critical changes to prevent the wobbling that existed on previous 650 Yamahas. First, the swingarm was lengthened an inch and beefed up for more strength and rigidity. The frame is now heavily gusseted around the swingarm mount, steering head, and rear engine mount.

The longer swingarm increased the wheelbase to 56.5 inches. The 650 retains its 27 degrees of steering head angle, but the front wheel trail has been increased from 3.9 to 4.4 inches, due to the shorter fork offset. But even with these new frame changes, the TX650A possesses a strange chassis combination that makes the overall handling really different from the street bikes we’ve previously tested.

The TX is still a 474-pound heavyweight, and it is still noticeably top heavy. 45.7 percent (217 pounds) of the weight rests on the front wheel, and 54.3 percent (257 pounds) is on the rear.

The high center of gravity adversely affects the bike’s slow-speed cornering, low-speed maneuverability, and directional stability in crosswinds. As you go through a slow turn, the bike sits up slightly and heads toward the outside of the comer when you open the throttle. You must make a small, quick steering correction to keep going where you were aimed.

The bike doesn’t veer off course a great deal, but enough to be annoying.

Yamaha stiffened the 650’s front forks and rear shocks, which successfully improved its high-speed cornering through smooth turns. The bike never wobbled at high speed nor did it do anything unusual in these turns. You can pick a line through a smooth corner and the machine will follow it precisely.

The footpegs and mufflers are higher this year, so we could lean the bike over much further without encountering premature grounding problems. If you play racer and push the machine to its limits, you will drag the footpegs when rounding smooth, slightly banked turns. Through fast, flat corners, the sidestand will drag when turning left and the muffler mounting bolt scrapes when going right.

If you’re a more casual rider, you can achieve reasonable lean angles without anything digging into the pavement.

The TX650A cruises along smooth highways and open roads nicely. You can change lanes quickly and predictably, and zip in and out of traffic with ease.

COMFORT AND RIDE: For hour-long trips, the TX650A is comfortable; but on longer jaunts, it becomes very uncomfortable, mainly due to the thinly-padded seat. The seat is hard and slants down at the front, so as you ride along, your body gradually moves toward the gas tank. In this area, the seat padding is thin and doesn’t offer much support.

You can feel the seat base pushing on your rear end, and after a short while you feel some saddle sores forming. If you move back on the seat, there’s a little more padding, but still not enough to be really comfortable. The stiffness of the suspension made the hardness of the seat even more annoying. The inability of the forks and shocks to absorb small bumps and ripples caused the bike to bob up and down, which hammered the seat against our butts.

On our test bike this was very aggravating: but on the borrowed 650, the broken-in suspension was considerably smoother. Solo riding on the borrowed bike was just about as smooth and comfortable as two-up riding on the test bike-and that wasn’t bad at all. And even though the suspension on our test bike is insensitive to small-and medium-size bumps, strangely enough, they absorb big jolts fairly well without transmitting much shock to your body.

The handlebar/footpeg/seat relationship is fine for people shorter than 5′ l0, but some long-legged riders will find it a bit cramped. The handlebars are high enough and have a nice rearward rake, but you’ll find yourself sitting in a squat position, with your knees high and sharply bent. This eventually makes you uncomfortable and restless.

Engine vibration also has a negative effect on the TX650A’s comfort. You get a tingling sensation through the hard, thin handgrips, and through the rubber-covered, rubber-mounted footpegs; but the largest amount of vibration comes through the seat.

One nice thing about the TX is its quietness. There is very little mechanical noise produced by the engine, and the note from the mufflers is a deep, throaty one. Our decibel testing showed that it produces only 86.3 db (A), so you won’t offend any citizens with loud, unwanted noise.

BRAKING: The Yamaha’s front disc brake worked perfectly and consistently during the whole test. It required only a two- or three-finger pull on the lever to bring the bike to a stop, and it never wanted to lock up the front wheel.

Although the rear brake isn’t very powerful, it does an adequate job of stopping the rear wheel. You have to press hard on the brake pedal to stop the bike, so you should never lock the rear wheel accidentally.

The brakes work nicely during panic stops. They’re progressive and stop the bike quickly and predictably without fading. The bike also doesn’t get sideways or out of shape when both brakes are full on; it stops in a straight line every time.

From 30 mph, we got the TX to a screeching halt in 37 feet 1 inch, and from 60 mph, it took 137 feet. The testers never felt apprehensive about using the full stopping power of the brakes because they worked so predictably. A beginning rider will also find the brakes reliable, consistent, and easy to use.

RELIABILITY DURING TEST: We were very pleased with the TX650A’s reliability. The machine spent some punishing hours at the dragstrip and on the dyno, plus many miles on the streets and highways. Nothing broke, fell off or stopped working, and that’s what reliability is all about.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION: The TX650A has a rugged, quiet engine that produces a wide band of usable power ranging from 2000 to 7500 rpm. Once over 10 mph in first gear, it pulls steadily and strongly all the way up to top speed. The close-ratio gearbox provides even gear spacing, and a short, positive lever throw.

The handling is unusual, with a high center of gravity that makes the bike feel top-heavy in slow turns, awkward while maneuvering at walking speeds, prone to be affected by sidewinds, and reluctant to be tossed into a hard corner too quickly. When the TX650A is new, the forks and shocks are stiff, causing the bike to skip around and change direction while cornering on ripply or mildly choppy pavement.

After the suspension has a few thousand miles to loosen up, the 650 corners more precisely on these same turns. And smooth, high speed turns create no problem, either when the bike is new, or after the suspension wears in.

The TX650A has the potential to be a true sporting bike in the tradition of the British twins that it originally copied. It has bettered these bikes in many areas — electrics, electric starting, oil retention, reliability and ease of maintenance. But if there’s one thing that these almost-extinct British bikes have going for them, it is near-impeccable handling, and in that respect, the Yamaha should have to stay after school for some extra lessons.

Okay, that’s quite enough of that! Many of the characteristics of the ’74 carried over into succeeding models, with incremental improvements over the years. So you’ll recognize many of the Yamaha XS/TX traits in your own bikes, for better or worse.

Yamaha TX750: The mysterious big brother

The TX750 was a Yamaha motorcycle made in 1973 and 1974. It was loosely based on the XS650 but had what Yamaha called an Omni-Phase balancer to counter vibrations which are inherent in a parallel twin with the crankshaft set at 360 degrees (both pistons rise at the same time).

Using a pair of balancers (one to stabilize the imbalance of the cylinders, the other to counter the rocking caused by the first balancer), Yamaha’s Omni-Phase balancer eliminated vibration in the TX750, producing a smooth ride previously thought possible only in a triple or a four cylinder. This new system was a first for a Motorcycle but resulted in massive failures for the first model year. Although these problems were fixed in 1974 sales never picked up and the machine was shelved.

Cycle World magazine, in their October 1972 issue positively reviewed the concept when they wrote: The result is smoothness beyond belief,. Shut your eyes and you are on a four. It couldn’t be a twin.

In addition, the bike was set up with a single front disk brake with provision to install a second one on the other side. European machines were delivered with twin disk brakes from the factory. The bike also had an interesting warning light system with a brake pad wear indicator, a first for a motorcycle.

The bike was popular at first but soon reliability problems began to emerge and the problems lay with the Omni-Phase balancer: At high rpm the balance weights would whip oil in the sump into a froth, aerating the oil and starving the crank for lubrication which resulted in bearing failure.

In addition, the balance chain would stretch, resulting with the counterweights being out of phase and making the engine run rough. Although Yamaha quickly repaired the problems, including a deeper sump and an adjustable balance chain, sales fell and the TX750 became synonymous with poor design and reliability.

The 1974 Model was extensively modified with a revised sump and does not suffer from reliability issues Thoroughly up to date, the Yamaha TX750 wore a single front disc, with provision for a second already built into the left fork leg. Starting was electric, and shifting was courtesy of a five-speed borrowed from its smaller brother, the newly-named Yamaha TX650. The blocky, almost chiseled-looking overhead-cam engine was all new, with a unique cast-aluminum exhaust manifold that doubled as a balance tube, further smoothing out the pulses from the counter-balanced twin.

If this wasn’t enough to get the Yamaha TX750 some ink, a controversial trio of lights housed between the bike’s speedo and tach, a “diagnostic panel,” made sure the new model was noticed. Oil pressure warning lights were nothing new, but Yamaha upped the ante by including not only an oil light, but also a rear brake lining warning light and a rear brake light warning lamp.

The brake lining warning light would set when lining thickness dropped to 2mm or less. But the brake light warning lamp came on whenever the brakes were activated. If the rear brake light burned out, the warning lamp would flicker madly every time the brakes were hit.

If the rear tail lamp burned out the brake light would light, but dimmer than normal, and the warning light would stay on.

While some riders saw this as a positive move toward onboard diagnostics, more thought the system was just plain stupid. “It does strike us that a red light that comes on when things are working satisfactorily might be a bit much, especially when the same light flashes when things get out of whack,” Cycle said in its March 1973 issue.

Unfortunately, talk quickly turned sour as TX750s started blowing up crankshafts. Ironically, the problem lay with the very feature that made the bikes special, the Omni-Phase balancer: At high rpm the balance weights would whip oil in the sump into a froth, aerating the oil and starving the crank for lubrication.

Compounding problems, the balance chain tended to stretch, knocking the counterweights out of phase and making the engine rougher than a standard twin. Yamaha quickly devised fixes for all of these problems, including a deeper sump and an adjustable balance chain, but the damage had been done. As quickly as the TX750’s star had risen, it dropped to the ground, the model’s name quickly becoming synonymous with poor design and poor reliability.

- 2011 Yamaha V Star Custom motorcycle review @ Top Speed

- 2013 Yamaha XJR1300 Review

- Frugal Fuelers: Yamaha WR250X – First Look

- 2010 Yamaha V-Max VMX17

- WSB Season Review – Motorcycle Race YAMAHA MOTOR CO., LTD.