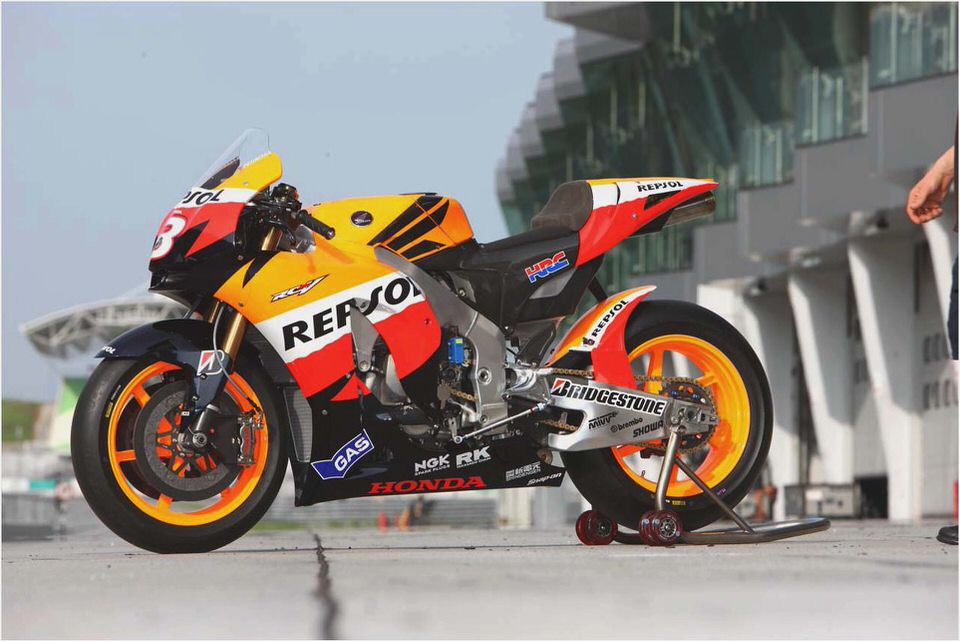

Honda secret MotoGP RC212V transmission revealed

146-1104-+scoop-honda-motogp-transmission-revealed+5.jpg

Ever since the beginning of pre-season MotoGP testing, trackside observers noticed that the factory Honda RC212Vs sounded different—notably, that their gearshifting was almost imperceptible. Instead of the usual hesitation and “pop” during shifts caused by unburnt fuel being ignited when the ignition system came back online (“powershifters” momentarily cut spark to interrupt power which allows a conventional transmission to accomplish an upshift without backing out of the throttle or using the clutch), the Hondas simply changed engine note in an instantaneous and nearly indiscernible fashion. Immediately claims of Honda using a version of its electronic DCT transmission used on its latest VFR1200F made the rounds, but the problem there is that MotoGP regulation prohibit use of any “purely electronic means of gearchange”.

FIM Technical Director Mike Webb was reportedly shown both the drawings and the actual transmission in a closed-door meeting by Honda reps to ensure that the transmission was indeed legal. More secrecy is kept by having only one Honda technician change gearsets at MotoGP; no one other than this HRC employee is allowed to remove the gear cluster cassette to change a gear ratio on any of the factory Hondas ridden by the Repsol Honda squad, or San Carlo Honda Gresini’s Marco Simoncelli, who is also provided with a factory RC212V.

Numerous theories and conjecture have since abounded on the Internet, but no real solid lead on the transmission’s construction has been found. Until now…

Thanks to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s website () as well as Google Patents (), any and all patents applied for can be found in complete detail in order to allow inventors to search and see if someone has already discovered their idea. A little creative searching nets you some interesting information, but it takes some effort.

By “creative searching”, we mean that corporations know people scour the USPTO site every day looking for corporate secrets before they’re officially unveiled, so they intentionally file the patents under names and descriptions that are as off-subject as possible. Thus, you won’t find this patent under “Honda” or “HRC” or “MotoGP”.

A particular patent applied for by a Mr. Matsumoto (who has several other patents, some under Honda Japan and others by himself) shows a transmission that uses an innovative cam/pawl setup inside the countershaft itself to engage transmission gears (similar to the Xtrac IGS, a company that works with Honda’s IndyCar engine program) rather than sliding the gears across a mainshaft as with a conventional constant mesh sequential motorcycle transmission.

However, the Japan Patent Office website () shows a patent applied for by Mr. Matsumoto and another engineer for an identical transmission design—only it also reveals that Honda owns this patent. There are several diagrams on the JPO patent application that show the device on a V-engine case, one that looks very close to the RC212V engine.

Which is substantial evidence that this is indeed the transmission on the factory Hondas.

A conventional sequential constant mesh motorcycle transmission changes gears by sliding one gearwheel across a mainshaft until it locks into a driven gearwheel via internal “dogs”—lugs cast into one gear that fit into holes in another gearwheel. Moving the gears across the shaft is accomplished by “yokes” or “shift forks”, which are controlled by a shift “drum”.

Because the dogs are made so that the gears lock together under power, power must be interrupted so that the gear wheels can be disengaged. Sliding the gearwheels across the shaft requires time as well.

With the Honda multi-stage transmission, there are no shift forks, and there is no lateral movement of the gearwheels. Instead of using dogs cast into the gears to lock them to the countershaft, the Honda setup uses a series of cam-type rods that slide back and forth inside the countershaft itself. The cam-type control rods actuate swingable pawls inside each gear that lock them to the countershaft when a gear change is enabled.

The pawls and the steps machined into the inner portion of the gears are designed in such a way that when the next gear becomes engaged, the pawls on the previous gear detach naturally. This means that there is no power cut needed, power is continuously transmitted, and no clutch actuation is necessary.

Because there is no large shift drum to control the shift forks, and since the gearwheels do not slide laterally on the countershaft/mainshaft, the gear cluster can be made more compact. The gears can be made stronger as well, since there is more room for gear teeth width.

The patent—like most of its kind—is a huge and tedious 30,000-word document that goes into excruciating detail of the transmission’s design and how it functions. Because it is drawn up in extensive legalese however, it can be quite a job to decipher even the most basic premise, as 40-50 words are used to describe something that can be stated in 10, and many paragraphs have repeated introductory sentences for legal purposes.

Interestingly, we found one paragraph that states the multi-stage transmission cannot be downshifted under power (as well as not be upshifted under deceleration). Whether naturally by design or otherwise, unless there is an electronic intervention that we haven’t found in the patent yet (which is quite possible), if you make a mistake on your upshift, you can’t just bang it back down a gear to get the rpm up unless you back out of the throttle.

When veteran journalist Henny Ray Abrams asked Dani Pedrosa and Casey Stoner at Qatar about the transmission in their RC212Vs, he got some interesting answers. “It’s smoother,” said Pedrosa. “Basically when you are in the corner, the shifting it’s a little smoother so the bike doesn’t do so much like this (pumping with hands). So if you are changing with bikes or maybe this corner going up, the bike is not shaking so much on the shifting. So this is something positive, because the shock is not doing any reaction aggressively and the traction is more stable.” We’d heard that the factory Honda riders were complaining about downshifting with the new transmission, and when asked, Pedrosa concurred, “sometime, yes.”

Stoner agreed that the new transmission helped, but noted that it’s not the magic pill that is responsible for Honda’s current domination of the MotoGP class. “Changes gear a little bit faster, it’s just smoother basically,” said the Australian. “Instead of a big clunk, it sort of just progresses from one to the next a little bit faster. But yeah, for me the bike’s no faster, it’s just smoother.

So when you’re on the edge of the tire, when you change gear it doesn’t make the bike quite as unsettled. In the past when there’s a gap in the thing, it makes the bike sort of unsettled. But with this one there’s a smaller gap and it’s a lot quicker so you don’t have the bike moving so much. And this is its advantage. It gives you better feeling, better feedback.

Yeah, for me the way it works is nice, but definitely not the race-winning solution.” Stoner also agreed that downshifting was an occasional issue. “It’s also a little bit aggressive coming back gears (downshifting). Sometimes you struggle to get back gears. Coming back a gear sometimes I find it a little bit difficult, but going up the gears it’s nice and smooth.”

- Road Test: Honda ST1100 v. ST1300 – Road Tests – Visordown

- 1998 Honda CBR 900 RR –

- How to Lower a Honda Civic eHow

- Honda Bikes in India

- 2006 Civic Concept Honda Si Sport