Otto Cilindri: Moto Guzzi V8 Grand Prix Racer Fast, fragile, flawed and fantastic, the Moto Guzzi V8 of the 1950s should have ruled Grand Prix racing. But it didn’t…

Photographer. Cycle World Archives, Moto Guzzi, © Morton’s Media

The Guzzi V8! If you dabble the least bit in motorcycling history, you have heard of this complex and ambitious machine, built in 1955 to dominate 500cc Grand Prix racing.

At its best, the V8 had the numbers to do it. In 1957, when Gilera and MV were making no more than 67-70 horsepower from their inline-Fours, the V8 could summon 80 crankshaft hp at just over 12,000 rpm—a power level not reached again in GP racing for 10 years. It had staying power, being liquid-cooled at a time when every competitor was air-cooled.

It was extremely fast—timed at 178 mph at the 1957 Belgian GP.

Yet it never won a single Grand Prix. Although fast on certain courses, it DNFed often. The V8 was a classic case of an ambitious program whose development needs exceeded the resources of its creators. The list of such failures is long—think of BRM’s V16 Grand Prix car engine of the 1950s, Honda’s oval-piston NR500 of the ’80s, Chrysler’s IV-2220 inverted V16 aircraft engine of 1944.

The engineering problem is to advance the state of the art by enough to win but by no more than can be made ready for use in the time available.

An astonishing five months elapsed from the moment when Guzzi principal Giorgio Parodi gave the project his approval until the first engine ran. Thirty days later came the first track test. Lead engineer Giulio Cesare Carcano, assisted by Umberto Todero and Enrico Cantoni, followed a logical path to a V8. Guzzi had nothing competitive in the 500cc class.

Its “bicilindrica,” the 120-degree V-Twin that had won the TT in 1935, had been retired as too slow in 1951. Its replacement, a liquid-cooled longitudinal four-cylinder, had been troublesome and ill-handling, winning only one GP. It was retired in 1954, leaving Guzzi with what it did so well: light, agile Singles with broad pulling power.

With such Singles, Guzzi won 350cc world championships 1953-57 inclusive, defeating DKW’s 10,000-rpm two-stroke Triple and Gilera’s transverse inline-Four.

But Gilera and MV were entrenched in the 500cc class, with highly developed Fours whose handling had benefited from the knowledge of transplanted English riders like Geoff Duke and John Surtees. These intelligent rider/engineers carried with them understanding of what had made Norton’s venerable Single so good in 1950-52—a strong chassis, forward engine position and supple hydraulic-damped swingarm and telescopic front suspension.

Guzzi’s 500cc Single might win an occasional GP (as Bill Lomas did at the Ulster TT in 1955) but never a championship. Carcano knew that Singles and Twins were finished in 500. Horsepower is basically cylinder-filling ability multiplied times rpm, so if Guzzi built another four-cylinder, it would confront all the development already completed by Gilera and MV.

To make up for the opposition’s experience in filling the cylinders of its Fours, any Guzzi challenger would have to be capable of higher rpm. That, in turn, would require a greater number of smaller, higher-revving cylinders.

Six? A Six would be wide, and European tracks—still based upon public roads in many cases—emphasized top speed and aerodynamics. Increased width was unacceptable. Then a V8?

Only water could cool the rear cylinder bank, but sketches and estimates soon showed that such a V8’s crankshaft would be less than 13½ inches wide. Even adding two inches for the dry clutch and 2½ inches for a water pump, the resulting package slid into a fairing an inch narrower than a modern Ducati V-Twin’s. Who could resist?

Don’t think of Guzzi as a quaint little European manufacturer quietly crafting oddities in a backwater. At the time, Guzzi had 800 machine tools on its production floor and was a major transportation producer. On staff were craftsmen in every specialty.

The company had produced aircraft parts in the war and understood how to quickly push projects from paper to metal.

The V8 engine is a beautiful object, and its details reveal Carcano’s devotion to weight control. The magnesium unit crankcase is open on right and left, allowing the crank to be slid in sideways. The middle three of its five main bearings were then bolted up against main webs at the apex of the Vee.

There are no separate cylinder blocks. A portion of the cylinder water jacket was formed as part of the crankcase, and the rest was cast as part of the cylinder heads. The outer main bearings were carried in right and left engine covers, which also supported the vertically stacked gearbox.

Wall thickness of crankcase and covers was 4mm—under 3/16 of an inch—foundry work of a high order.

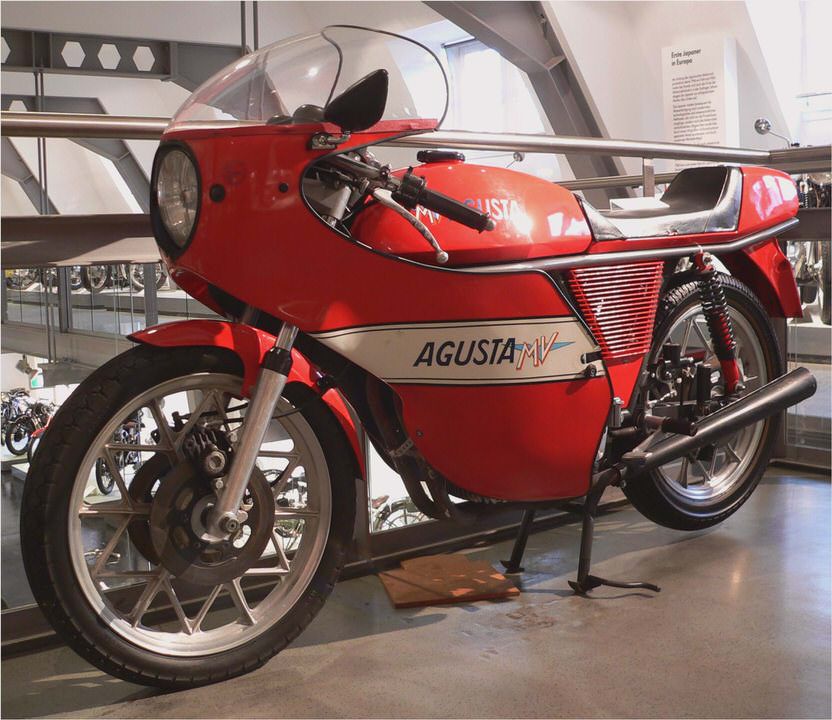

- The 2010 MV Agusta BRUTALE 1090RR Motorcycle

- For Sale: 2003 MV AGUSTA F4 S 750 in MV Agusta F4/Brutale Bikes For Sale Forum

- 2013 MV Agusta Brutale 1190 First Look Review

- 2013 MV Agusta Brutale 1090 RR Review – Quick Ride

- Memorable Motorcycle: MV Agusta F4 750 – Motorcycle USA