The Perfect Compromise?

Amsterdam, November 16, 1999 — Know what that is? said the Triumph guy as we circled the stationary Sprint. None of the journos notice it when they take the Sprint, he said shaking his head in amazement as he leaned forward to pull open a small plastic cap low on the right-hand side of the bike. It’s even got a plug for your heated touring gear.

Then he stepped back to give me room to admire this example of the commitment with which Triumph has set out to build their new generation sport touring bike. Courtesy forced me to pause for a few seconds in silent admiration, but an access plug wasn’t what I was looking for from the bike. There would have to be more than that — a LOT more — if it was going to come even close to deposing the Honda VFR800, the long-reigning King of the Sport Tourers.

There’s been a Sprint in Triumph’s line-up since 1993, but the arrival of the new generation T595 Daytona in 1997 created a sales slump as the Sprint struggled to find a place between the new Daytona and the full-dressed Trophy. A large dose of new technology was needed to solidify Triumph’s place in a market segment that is small but relatively uncrowded. The most obvious strategy would have been to do some minor work on the Daytona to take the edge off the sporty character of the bike.

The Sprint pulls strongly from just off idle to the 9500 redline with the rev limiter kicking in almost immediately after.

But the problem was that nagging doubts about the Daytona chassis led to its recall in 1997 after a couple of bikes had the headstock fracture under severe crash conditions. After that experience, Triumph had decided to bow to fashion and use a conventional twin-spar frame for the upcoming TT600. Possibly its application on the Sprint would give Triumph a little time to sort out any problems before they launched the bike on which their future in the new millennium firmly rests.

So twin-spar aluminum perimeter frame it is, with a wheelbase slightly longer than the Daytona and some tweaks to the steering geometry. The back end, including the single-sided swingarm, has been lifted from the Daytona and lower-spec suspension grace the front and rear.

The engine is close to the 955i unit, but with the inevitable changes such as new cam profiles to soften power delivery as well as suitable fuel injection re-mapping. Triumph claims to have cut power to 112 bhp from the Daytona’s 130 bhp, but they kept the torque high and flat around 65 ft lbs. from 3500 rpm through redline at 9500 rpm. We were unable to get the Sprint to the dyno to check the figures, but the seat-of-the-pants dyno says these numbers are in the ballpark.

What Triumph has definitely managed to cure is the hole in the power delivery that the first T595 had at 4000 rpm.

It’s strange that Triumph hasn’t given the Sprint any over-rev capability since the bike is still pulling hard and a few more revs would be appreciated by sport riders on a charge. The Sprint can be ridden on the edge but it’s hard work. With a dry weight of 456 pounds and the new standards for sportbikes set by the R1 and copied by the new CBR929RR and GSXR-750, a few people might consider the Sprint positively obese.

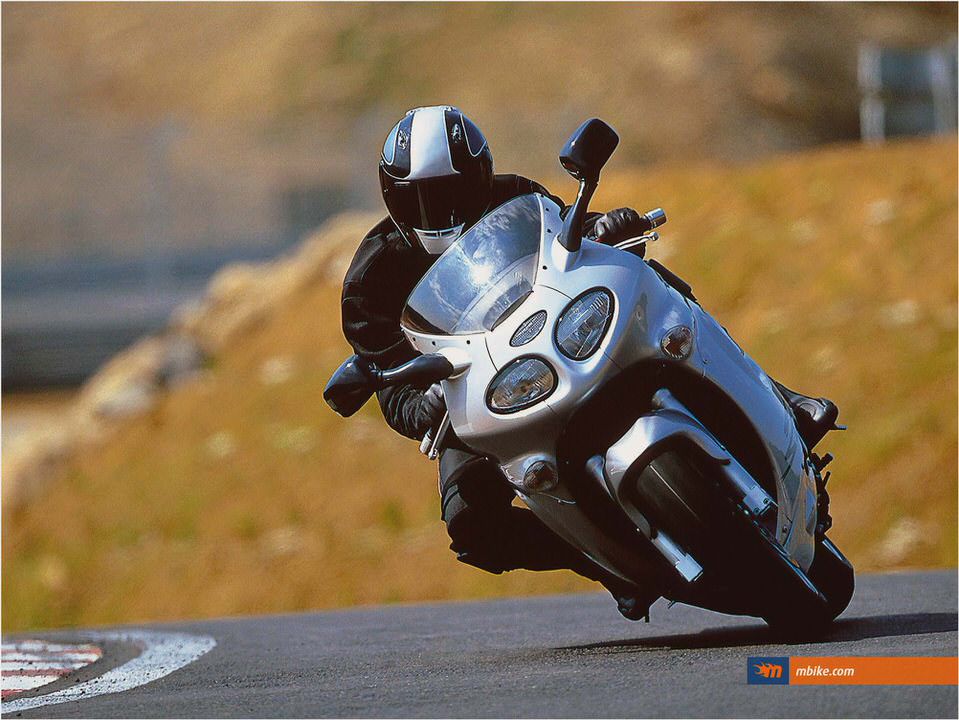

Still, it carries its weight well and once turned into the corner tracks like a rhino on a scent trail, although the worn Bridgestone BT57s got quite loose mid-corner.

Turning in needs a determined push on the bars and flip-flops have you wishing you did more with your physical condition than check out Men’s Health every month. Identical brakes to the units found on the 955i do as good a job despite the extra weight. If your friends ride anything but the latest generation of hypersports bikes, you should be able to use the ample brakes and motor to keep them within sight. But the Sprint’s not really about scratching on Sunday mornings.

It’s about riding 400 miles on Saturday to do some scratching on Sunday morning, then riding 400 miles home again on Sunday afternoon.

It has many of the qualities that you need from a bike to even consider such a proposition.

The riding position is excellent, with the wide, flat bars exactly right. The mirrors are mounted well out into the slipstream and do more than let you admire your elbows. But you have to watch them when lane splitting on gridlocked highways or else they’ll snag on car mirrors, hands holding cigarettes, dogs, kids heads or anything else sticking out of cars full of stressed-out occupants.

The bike’s well-balanced and good at slicing through traffic since the clutch is light, the gearbox is smooth and the engine is full of grunt with perfect fuel delivery. When the traffic clears, nail the throttle at 5000 rpm and cruise at 100 mph all day — at least you could if the seat were better padded. Our test bike had 10,000 miles under its belt and the foam had started to settle.

Sitting on a lightly-padded sub-frame is not comfortable.

Also, in true Triumph tradition, the vibration through the bars will leave you with a numb right pinkie after an hour, so a stop every hour would be welcome.The Sprint is incredibly fuel efficient turning in 45 miles per gallon on the highway and not dipping much under 40 mpg on the backroads. Good for the pocket if not for the butt. So there’s some niggly stuff on the comfort level, but the rest of the vital ingredients for an excellent sports tourer seem to be present and correct.

Despite this bike’s generally high-level of all-around goodness, it’s difficult to feel passionate about the bike.

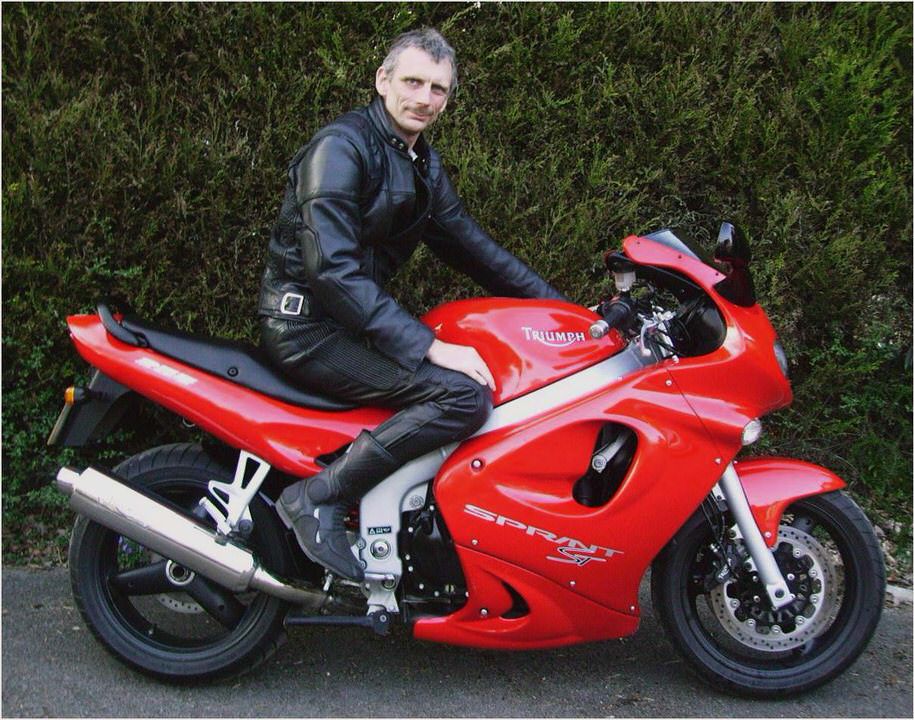

It’s competent at everything but seems bland and dull all the same. There is nothing to give the bike any sort of character.Even the potential excitement from the snarling 3-cylinder engine is smothered in the technical efficiency of the exhaust system. The styling itself, especially on the black model, is very restrained, reinforcing the perceived dullness of the bike.

It’s not a bike to turn heads; it has them nodding instead. Small wonder that in Europe the red color option outsells the black two to one. For the 2000 model year blue will be offered as well.

So has the Sprint snuck up on the VFR and stolen the honors in the sport touring class? It comes close, but lacks the quantum leap of distinction that will seriously dent the momentum of VFR sales driven by 15 years of Honda’s market domination. Yet Honda has left themselves vulnerable. The lack of a factory hard bag option is, at least to a few Stateside journos, a serious flaw.

The BMW R1100S is an excellent machine, yet with all the touring options the retail price begins to approach Harley-Davidson territory.

They could well be King of the Sport Tourers.

Ducati did a good job when building the ST4 around the 916 engine with the engine and chassis and integrated hard bags matching the sporty good looks. But Ducatis are sportbikes and expensive and 916 engines have been known to go pop as well. Functionally, the Triumph can scarcely be faulted.

If only the styling had been a little more creative and some magical ingredient added to reinforce the sportier side of the bike’s character, they could well be King of the Sport Tourers. For the time being the Sprint is just heir apparent.

- Motorcycle Specs

- Triumph Trophy – What to expect from an older Triumph Sprint Executive?

- Triumph Bikes – 2013 COLOURS CONFIRMED motorcycles marketplace…

- Triumph Rocket III Roadster Review – Autos.Answers.com

- Triumph Sprint Executive Chain And Sprocket Kit, Cheap Triumph Sprint…