Kawasaki ZXR 750 (August 2002)

Flawed genius? That’s a widely-held view of the Kawasaki ZXR750. Who better then than ROB SMITH to give us all we need to know to purchase the bike?

If you’d regularly found yourself by the side of a twisty mountain road in 1989, chances are that at some stage you’d have been blown away by the sight and sound of a howling lime green blur. Momentarily hovering low to the ground, rasping and shrieking away into the distance leaving your senses reeling with one question in your mind. What the pharrrkwazat?

Zat, was the Kawasaki ZXR750 H1.

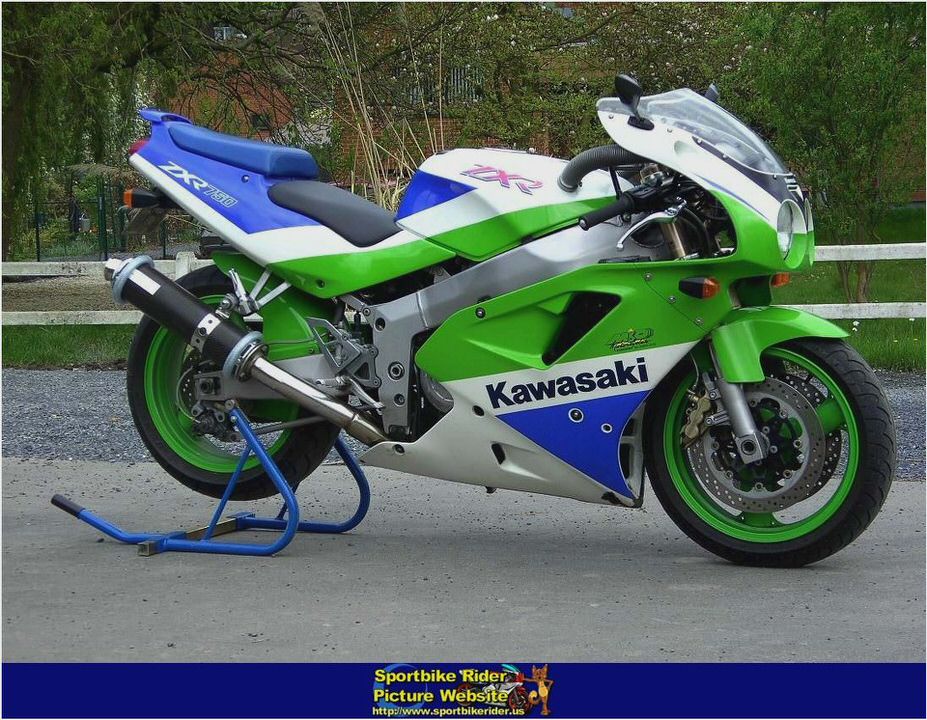

Embodying outrageous ability with gorgeous styling, the ZXR is still a boss motorcycle that, for its entire six year life in Australia, went as well as it looked and provided Kawasaki race-rep fans with a class alternative to the GSX-R or the pricey Honda RC30.

HISTORY

Back in 1988 the special K factory decided that the 16-valve, liquid-cooled, in-line four residing in the dull, but far from pedestrian GPX750 would realise far more of its potential slotted between a new twin-spar alloy chassis with some trick suspenders, and a new sharper look. And so it was in 1989 the ZXR was born.

Having had a bit of judicious tuning, the 748cc ZXR, making about 95PS, emerged blinking into the daylight wearing a bank of four 36mm Keihins fed by a pair of trick looking inlets in the fairing.

Suspension was attended to by conventional forks adjustable for preload and rebound at the front, and a Uni-Trak monoshock, adjustable for preload and rebound damping at the rear. Wheelbase was a short 1410mm, with castor and trail set at 24.5° and 100mm.

Clothed in green, white and blue or red and black it was a visual king hit.

1990 saw an H2 version with a swag of changes that included carb size growing to 38mm. Wheelbase gained a significant 35mm, while inside the engine there were longer conrods and shorter pistons to extract a bit more power. The swingarm was changed and a new, more race style pipe added to the looks.

Strangely, although the wheelbase was now longer, the swingarm struggled to compress the rear suspension resulting in a rock hard ride.

1991 heralded the completely restyled J1 into the arena. Bore and stroke had changed from the previous 68 x 51.5mm to 71 x 47.3mm to produce a capacity of 749cc. USD forks were adjustable for rebound and ride height, the rear shock remained uncompliant, and trail dimensions went down from 100mm to 95mm.

Wheelbase shrank again to 1420mm.

Inside the engine, Kawasaki’s engineers had hammered the overtime resulting in a mass of changes that improved midrange, but perversely had cut actual peak power. Did it matter? No not really, it was still a very fast machine.

1992 saw little actually change on the J2, other than an attempt at sorting the utterly inappropriate rear shock with softer springing and damping.

1993 saw the much-improved L1 take up duties where the J2 left off. The big news centred around the Ram -Air system, new pistons, cylinder head and cams which boosted midrange and top-end power. Geometry changed yet again with rake and trail now at 25° and 99mm, and the wheelbase measuring 1430mm.

Rear suspension, although marginally better, was still crap on anything that didn’t have the smoothness of a pool table.

1994 and ’95 were years when the ZXR did very little other than change its threads for variations in colours and graphics. Something big was obviously coming from the factory, and 1996 saw the results of all the development done over the ZXR’s six years with the ZX-7R, an all new remake of a fantastic bike that tends to get passed by in the search for the latest and therefore greatest.

ON THE ROAD

Lets start with the H1. By today’s standards the H1 is a bit of a porker with a top heavy feel to it that makes you realise how far these sorts of bike have come in the last 13 years.

Despite the suspension being hard and fairly unkind to the rider, the chassis does it best to keep things stable right up to its top speed of around 240km/h.

Steering is precise but requires more effort than you’d like to use at the bars, around town this means stressed tendons and an almost psychopathic desire to line up some country roads. Unfortunately just when the urban sprawl ends and the ZXR should be in its element, the rear shock conspires to upset things by refusing to compress enough to absorb anything bigger than a an ant corpse. The result is that the ZXR leaps and hops around on bumpy roads, intimidating rather than accommodating.

Still, show the ZXR a fast open sweeper with little for the suspension to do, and the rigid chassis makes corner-carving an almost spiritual experience.

At last the opportunity to spank the motor hard reveals itself and down-shifting for any corner just to hear the exhaust note at 10,000rpm becomes the order of the day.

At a less frenetic pace and in newer company the early ZXR displays a somewhat less than inspiring midrange. It’s okay, but it never leaves you thinking ‘Heavens to Betsy, what’s happened to my arms!’

Brakes are good, and offer reasonable power and feel, which is just as well because the suspension certainly gives the tyre a good workout, especially on the approach to downhill corners.

So why would you buy one? Well, aside from the fact that it’s a great looking motorcycle, you don’t need to do a great deal to fix the suspension’s shortcomings. Once that’s taken care of it’s gorgeous, and represents a well-finished and affordable alternative to mega-buck new stuff and rewards an expert rider who’s prepared to take the time to get to know what it can do.

Jump forward a mere four years from that early bike to the ZXR750-L1 and it has developed into a completely different machine; but strangely the same. Along the way Robbie Phillis has finished third in WSB in 1991, and Scott Russell has taken the ZXR to victory at Daytona in ’92, and WSC in 1993.

It’s an animal.

Just about everything has changed and the Ram-Air now lends the already compelling induction noise a hollow resonance that starts with a low begging moan, and ends with a climactic shriek that begs you to give it all you can possibly can.

The engine still lacks the bottom-end and mid range of the competition, but the shrieking rush to the top-end as the power crawls out of the dip at 7-8000rpm is the reason why you buy a ZXR. That and the wonderfully balanced feel the bike has.

At a track day you’d shake your head in amazement that a bike that’s almost 10 years old can be this composed. Steering is now corner stabbing sharp, and turning while hanging late on the four-piston Tokico brakes is the ZXR’s stiletto up the sleeve. Just about every journo has written superlatives about the ZXR’S front-end control, and they’re right, it’s good.

The gearbox is a pretty clunky device but dependable, perfectly in keeping with the rough-neck engine’s riot-inciting behaviour. Sadly though, the suspension, while better, is still too damned hard for back road giggles and, in conjunction with the stretched-out riding position, will have you squeaking your order at the bar and nervously checking the contents of your leathers.

Is it cheap on fuel? Chances are you won’t care much, given the nature of the bike, but like its predecessor it’s okay. You can expect 200 kms to fill up when you’re right up it, and a bit more if you’re not.

Bottom line here is that the ZXR is a brilliant bike to own and ride if you’re a committed sports bike rider who’s prepared to sort the suspension, does a few track days and rides well-surfaced roads. Oh yeah, and it looks the bollocks too.

IN THE WORKSHOP

The ZXR750 in all its guises is a tough bike that’s quite well made and mechanically resilient to the kind of abuse that it gets. (Anyone that says they’ve never thrashed it should be eyed with a great deal of suspicion.) Given that the engine is a tough unit with a good reputation, let’s have look at what you’ll need to be aware of when buying one.

Because no-one buys a ZXR to just potter about, rev the bike at stationary and look for smoke on the over-run, which’ll be a sure sign that it’s been rung out from cold or with the front wheel higher than head height. Also the gearbox – anyone can do a mono in first gear, but getting from there into second and beyond can be a little more challenging. As a result second gear can take a hammering, so be sure to load up at low revs and then rev it out in second to make sure that it doesn’t jump out of gear.

Check the steering head bearings for play from cack-handed mono landings, and look for cracks in the fairing brackets from accident damage.

Make sure the rear shock hasn’t been adjusted with tools other than with proper C spanner and look for general signs of abuse and butchery all around the bike. After that look at all the bits that touch down in a crash, as these babies tend to get lobbed by those unable to control the wayward behaviour of the rear shock on a bumpy road. As far as servicing goes there are no nasty surprises.

MODIFICATIONS

Well it’s got to be that shock hasn’t it? The secret to eternal ZXR happiness lies in that one change. See your local suspension expert for advice. After that a pipe, jet kit and air filter will liberate a few horses, but most importantly will sharpen throttle response.

Personally I’d leave the pipe unless I’d damaged the original and had to have an aftermarket job, the standard noise is intoxicating and legal. You know it makes sense!

WHICH ONE?

The early ones were classically lovely, but for me it’s got to be an L1-L2-L3 in Kawasaki green.

Published. Friday, 30 August 2002

- Kawasaki KLX 250SF Long Term Evaluation

- Kawasaki VN 1600 Mean Streak-Kawasaki

- Kawasaki Vulcan

- ’01 1500 FI Drifter, no spark – Kawasaki Forums

- Höly Kawasaki ER-6 – Custom & Modified Bikes Bike News Motorbike Videos…