Related Content

Barry Porter’s Benelli Sei 750

Barry Porter discusses owning and riding his Benelli Sei 750.

Found on eBay: 1963 BSA Thunderbolt

Wandering through the expanse that is eBay, many things caught our eye this week, but we kept coming.

John Michael Sullivan’s 1969 BSA Rocket Then and Now

John Stratton shows us photos of his brother-in-law’s 1969 BSA Rocket, then and now.

1953 BSA Bantam

A 1953 BSA Bantam on display with other classic motorcycles at the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum.

I can still remember opening my copy of Motor Cycle News and seeing BSA’s full page ad for its 1966 motorcycle range. I was 15, motorcycle crazy and hot for motocross.

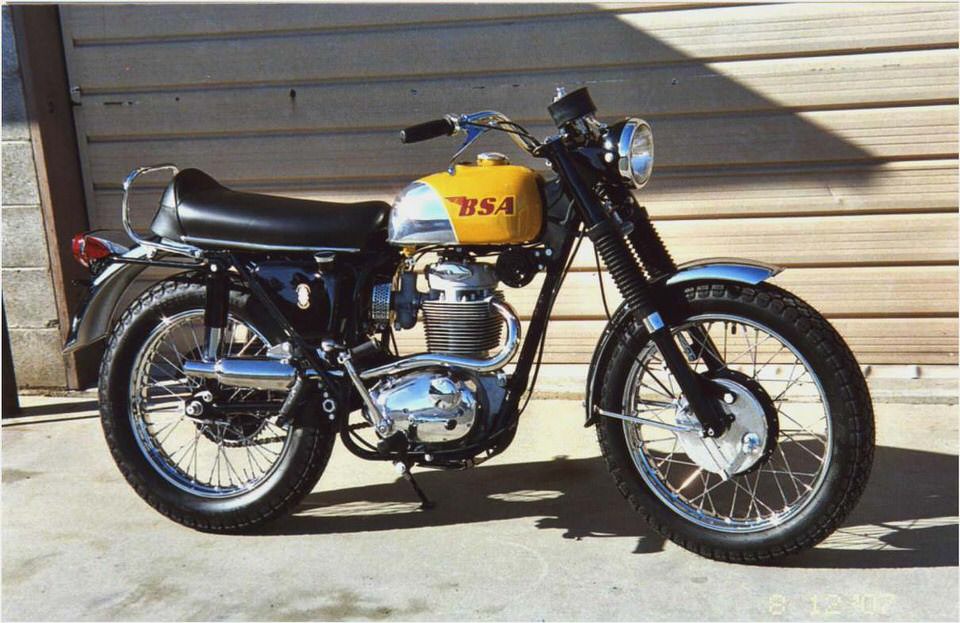

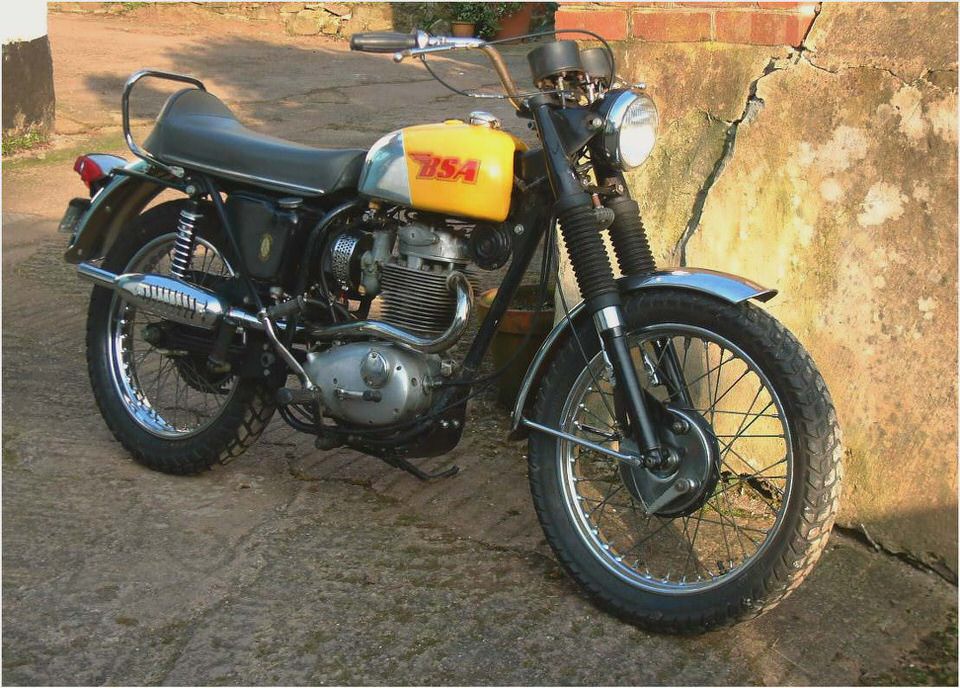

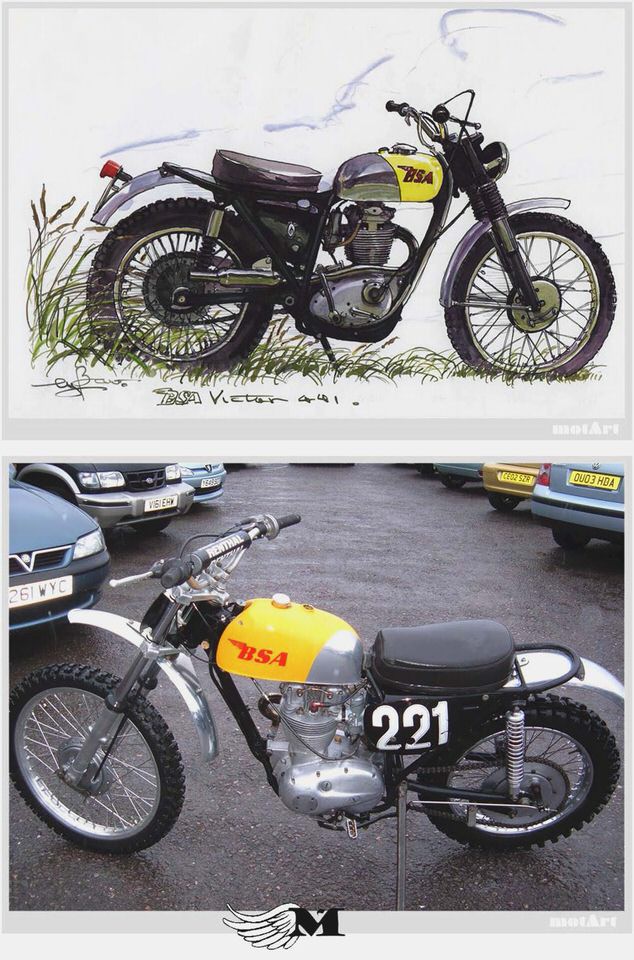

Jeff Smith had just won his second successive world championship on the 441cc single-cylinder BSA Victor, and to cash in on its investment BSA introduced a street-scrambler version of the Victor. It was chunky, aggressive looking and had a shiny, polished aluminum gas tank with a sexy swash of yellow running across the tank. I wanted one so badly I could scream.

By the time I turned 16 and got my bike license, the girls I was interested in preferred scooters to motorcycles — more chic, I guess, and less likely to spray them with oil — so that’s what I rode. Then I discovered the even more significant advantages of four wheels for cherchez la femme, so I traded my Vespa for a 1955 flathead Ford Anglia. But the lusting for a BSA Victor never completely went away.

It wasn’t long before I was back into bikes, and after a couple of years commuting on a Honda SL125, I decided it was time to move up. I tracked down a used 1969 BSA Victor in the classifieds, parted with my money and quickly became acquainted with the concept of buyer’s remorse.

BSA reality

Actually riding the BSA after my little Honda was a major disappointment. Where the Honda was slick, sophisticated and easy to ride, the Beezer was stark, clunky and ornery. I pretty much had only to look at the Honda and it would start, while I sweated away trying to kick the BSA into life. The Honda ran like a Swiss watch; the BSA shuddered, coughed and misfired.

Its favorite trick was stalling at traffic signals just as the light turned green.

Worse yet, I couldn’t find parts for it, nor could I find anyone who could help with knowledge or insight. And while Gold Stars and Vincents were becoming collectible, BSA unit-construction singles were just so much junk. The world had moved on, and the obsolete Victor was caught in the twilight zone between trash and treasure. I had become, I found out, a “victim.”

The Victor story

All BSA unit-construction singles (the gearbox is cast with the engine instead of being attached separately) trace their lineage back to the Edward Turner-designed 150cc Triumph Terrier of 1953, a simple, unsophisticated 4-stroke single intended as a cheap commuter that soon grew into the best-selling 200cc Tiger Cub. The BSA group, which had owned Triumph since 1951, adopted Turner’s design, and for 1958 BSA announced the C15, a new 250cc 4-stroke single based on the Cub with cylinder dimensions of 67mm by 70mm.

This proved a solid, reliable little bike, and tens of thousands of British teens cut their motorcycling teeth on one. It was cheap, cheerful and tunable, too. Before long the C15S scrambler was winning trophies in motocross, especially when piloted by BSA team rider Jeff Smith.

BSA next produced a 343cc version of the single, the B40, by increasing the bore to an oversquare 79mm by 70mm. The B40 also sold well, and became the British army’s standard motorcycle until being replaced in the 1970s by the Rotax-powered Armstrong. A sports version for 1962, the SS90, soon developed a reputation for fragility, perhaps indicating that the limits of the design were being approached.

This should have been a clue.

Meanwhile, in BSA’s competition shop, an even larger capacity version was being developed in the hope of gaining the 500cc world motocross championship. Experimental engines of 420cc and finally 441cc (matching a 90mm stroke to the B40’s 79mm bore) were produced. Jeff Smith rode a modified C15S-framed bike with the 441cc engine in 1964 and 1965, taking the 500cc world motocross championship both years.

The bike was christened “Victor,” and the following year, 1966, BSA introduced a production 441 Victor to the public.

BSA poured plenty of money into the Victor program in 1966 in hopes of taking a third championship against the challenge of the new lightweight 2-strokes. An experimental titanium frame reduced weight, but it was prone to cracking and the special techniques required to weld titanium meant it couldn’t be repaired in the field. The engine had also reached its reliable power limit, and East German Paul Friedrichs took the title on a 2-stroke CZ.

John Banks took up the challenge for BSA in 1968 and 1969 with a full 500cc machine, finishing second in the championship both years, but it was the end of the line for 4-strokes in motocross. Nevertheless, BSA had claimed two 500cc world championships with an engine that started life as a 150cc “tiddler.”

Life with a Victor

Though the Victor became popular as an offroad bike in the late 1960s, it had a number of fundamental flaws that plagued it over the years. First, the earliest street-legal models were little more than motocrossers with lights. They retained the 11:1 compression of the race bikes and were fitted with Lucas’ temperamental “Energy Transfer” battery-less ignition system.

Trying to kickstart a big, high-compression 4-stroke single with intermittent sparks was, to say the least, a challenge.

Second, the engine inherited its bottom end from the 350. The big end bearing was somewhat undersized for the job, leading to early bearing failure, while the light flywheels meant power delivery was rough at low revs. All this was OK for a dirt bike, but less so for the street.

The transmission, also from the 350, suffered, too: Bearings had a short life, clutch slip was always a problem, and the engine’s torque could bend the gearbox mainshaft.

By 1969, the Victor had become more street oriented, with lower 9.5:1 compression, battery/coil ignition and even a heat shield for the waist-level exhaust. For the purists it had sold out, but for the rest of us, it was a much better machine to live with.

Sadly, BSA finally got the big single street bike formula right, but only when it was too late for the company. Based on John Banks’ 1969 competition bike, the 1971 Victor 500 had a full 499cc engine of 84mm by 90mm with a larger big end, three main bearings and a strengthened drivetrain. The B50 engine was powerful, reliable and more user friendly.

But the same couldn’t be said for BSA, which went bust in 1973. Remarkably, the B50 engine was still being used as the basis for the British-made CCM motocross and trials machines until the early 1980s.

The knack

To make my 1969 Victor even more streetable, I’ve fitted a Boyer electronic ignition for a more reliable spark. I’ve also added a Norton Commando inline oil filter to ensure a clean supply of oil, and a larger countershaft sprocket (19 tooth instead of 17, and readily available from British parts suppliers) to reduce engine revs at road speeds.

I also had my carburetor bored and fitted with a brass sleeve on the throttle slide. This significantly extends the life of the carburetor — the stock slide will start to “gall” in the carburetor body because both parts are made from the same zinc alloy — and makes for much smoother running by minimizing air leaks. Together with regular changes with full-synthetic oil, the engine seems to be holding up well.

But I also avoid long stretches of highway, as it seems the combination of hot oil and extended running at high revs will trash the big end bearing. Ask me how I know.

There’s a trick to firing up a well-sorted 441 that makes it so easy, I’m sure I could start it by hand. The carburetor has to be “tickled” (shorthand for flooded with raw fuel) and the engine turned over (using the decompression lever) so that the piston is just past top-dead-center on the firing stroke (which is easier than it sounds). Then, with a firm, committed swing at the kickstarter with the throttle closed, a well-maintained 441 will almost always start first time.

If only I knew such things back then.

With modern ignition and the rebuilt carb, my Victor now starts easily and runs smoothly. It’s light and nimble in traffic, accelerates quickly (up to about 40mph, anyway), and the torque and rearward weight bias will easily hoist the front wheel. Fun. The brakes are excellent, and the handling is quick and secure: It’s great fun.

Sadly, the stock suspension is way too firm for any serious off-highway riding, but it works fine on gravel.

With gas prices rising and the Victor returning better than 60mpg, its time may be yet to come. Victim? Not me. MC

Press Reports

“The Victor. has the weight and general handling usually associated with 250s, while it does have the urge of a 500.” — Cycle World . April 1966

“The 441 single is a rare jewel of simplicity and a masterpiece of performance.” — Cycle . April 1968

“For those of us who like to potter about with old bikes, motorcycles like the Victor still deliver satisfaction in spades.” — Cycle World . August 1989

“Bash it, thrash it, even trash it, the 441 Victor was proof positive that the British could build a highly stressed, reliable power unit.” — Rider . July 1993

Resources BSA Owners Club

- 1957 BSA Daytona Goldstar Me & My Bike – Motorcyclist Magazine

- The Kawasaki Z1 Prototype – Classic Japanese Motorcycles – Motorcycle Classics

- SR500 Cafe Racer GearheadExchange Blog

- BSA A65 SS Firebird

- British motorcycle manufacturers B