MV Agusta F3

New Jersey Motorsports Park

July 18th, 2012

I was prepared to be disappointed.

Although I love Italy, I try not to be blind to its faults. The Italians have the most beautiful language, stunning lands, and majestic history. They have dragged all of western civilization into modernity not just once, but twice. They also have the tragedy of the Camorra, the ‘Ndrangheta, the Cosa Nostra, and Silvio Berlusconi. This balanced appreciation means that while I am savoring a slice of fresh buffalo mozzarella;.

I am also trying to taste for the telltale bitterness of illegally dumped toxic waste.

The Italians themselves refuse to purchase goods off the Internet (because you can’t check the stitching quality on line) as there is the ever present business temptation to take advantage of the out-of-country rubes that will buy suits with a Made In Italy label, (referring to the liner not the cloth), or Italian export market olive oil that is actually from Spain. These business practices are nothing new. It was over 2500 years ago that the Romans coined the term Caveat Emptor.*.

And so, after my own heartbreaking experiences with beautiful motorcycles that were simply styling exercises built around horrible excuses for metallurgy combined with highly optimistic material strength engineering (looking at you Moto Guzzi Lario 650, Ducati 748R, etc) I was prepared for the MV Agusta to be a lackluster performer with distractingly beautiful bodywork.

The company MV Agusta has had more owners in the last ten years than Italy has had prime ministers; Cagiva, Proton, Gevi and Harley Davidson have all had a turn. And the global financial crisis has been a double-edged sword for MV. While the crisis eviscerated the general motorcycle market along with its middle class purchasers, the luxury market has been largely unaffected.

More importantly, the Japanese Yen has appreciated 50% over the last five years while the Euro has steadily declined. In 2008 dollars today’s Japanese middleweight motorcycles would cost $7,845 (about what they did then) and an Italian one would cost about twice as much at $15,500. However, due to the exchange rate changes, a 2012 Japanese middleweight is $12,000 and the Italian ones are only a paltry $14,000, or barely 16% more.

If Germany would do the rest of Europe a favor and leave the Euro we would probably see Italian motorcycles priced lower than their Japanese competitors.

After multiple ownership changes and the GFC, MV ended up back with original founder Claudio Castiglioni in August, 2010. Claudio has been the constant design presence across all that time and, upon his (one can only hope) final acquisition of the brand, he was determined to change the small luxury brand from money hemorrhaging to profitable and increase the models and competitiveness of the marque.

So my contemplation while driving from DC to New Jersey was this: is this MV a great looking suit with bad stitching? A luxury lifestyle product for display? Or is it a real performance piece?

50.5% in the front, 49.5% rear. 381lbs dry weight.

Claudio began with a change in the company mission intended to move MV from the stratosphere into just high end. The highly successful Brutale heavy weight bikes were the start of that move to more moderately priced bikes. The 675 triple now continues that campaign in both sport (F3) and naked (Brutale) versions.

Make no mistake: rather than putting red bodywork on a tired old air cooled bike and cashing in, MV designers set their benchmark at the best of the Japanese, and then tried to surpass them, an audacious move for a company of 214 people.

The highest performance middleweight engine from Japan is the R6, whose engine weighs 134 pounds and puts out 127hp and 66nm of torque. The F3 engine weighs 114 pounds and puts out 128 hp and 72nm of torque. The F3 revs to 15,000 rpm.

With its short stroke crank the Italian triple revs 2,000 rpm higher than the Triumph 675 motor.

I was invited to ride the bike at the New Jersey Motorsports Park during the sweltering heat wave that desiccated the East Coast in July. The weather was brutally oppressive with 100% humidity and 100 degree temperatures. The track’s grass was brown and dingy, the air was thick and the light was flat.

MV Agusta’s entire US staff (all four of them) were in attendance and legendary tuner Eraldo Ferracci (of Fast by Ferracci fame) drove his humble box van the couple hours from his base in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.

American engineer Brian Gillen who lives in Italy and Italian tuner Eraldo Ferraci who lives in America.

The whole affair had a much grittier home cooked feel than the highly corporate, themed and polished launches of other, particularly Italian, companies. Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate opulence as much as the next guy but sometimes it feels that the focus of a company is on the lunch buffet, the souvenirs or, worse yet, the clothing line, and not the bikes themselves. I was expecting lots of references to the noble history of the MV brand and tchotchkes with the classic MV logo.

I got a bunch of hard core motorcycle enthusiasts and the ‘corporate’ guys doing the tire swaps. I liked it.

The bike comes stock with Pirelli Diablo Rosso II tires but we tested on Dunlop Q2s, principally because the Dunlop guys would send a truck with a tire machine. There were three bikes for nine riders so we would not have the opportunity to do too many suspension adjustments.

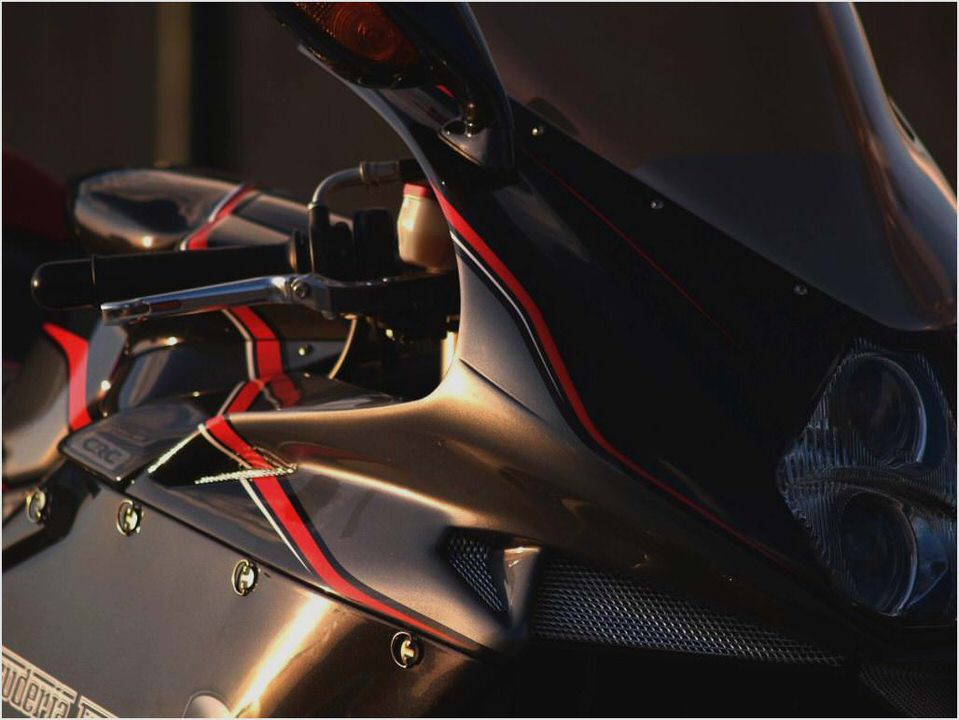

This single sided swingarm is as light as many of the current dual sided.

The ergonomics are largely based on an R6 so the bars are low and flat and the impression is very much of sitting on top of the bike, not in the bike. The seat is narrow, flat and hard which is just perfect for track use. The pegs are stylish and sleek which also means they are smooth and a little slippery a la Aprilia.

The pegs are actually comfortably low for a sport bike. The plastic gas tank is short, which accentuates the 50.5% forward weight bias and put one’s weight firmly on the wrists and the helmet above the steering stem. The bike feels tiny in all dimensions.

Engineer Brian Gillen points out to editor Sam Fleming how the 17 liter plastic gas tank extends under the seat as is current practice in World Superbike and Moto GP.

Thumbing the starter wakes up a clattering of mechanical noises. This is no Yamaha.

The ‘throttle’ is no throttle at all, it is simply a hall effect potentiometer measuring where the rider is twisting the grip. The signal is then mixed with a host of other CAN bus** data, which, after being filtered through the rider selectable engine response mode (Rain, Normal, Sport, Custom), opens the single butterfly throttle bodies and adjusts a host of other settings. Riding the unfamiliar New Jersey track in Normal mode the bike felt powerful and torquey with very tame engine response.

Repeated mid-corner on/off throttle cycles (resulting from the Where am I in this turn?” syndrome didn’t upset the bike in the least.

The F3 was entirely designed in CAD and has incredibly tight packaging, but with many of the oil and coolant lines cast into the cases and the CAN bus electronics, the final result is very clean and tidy. There are two injectors per cylinder but only a single computer-controlled butterfly. An external oil cooler is fitted.

These are about four times more efficient that the typical oil/water coolers used on other middleweights and, of course, more expensive.

My initial impression of the handling was mixed. The bike was nimble and very quick and responsive to side to side high RPM input but there was some vague underlying characteristic which was preventing me from totally trusting the front end and carrying a lot of lean angle.

The electronic quick shifter encouraged full throttle upshifts. I never missed a shift or hit a false neutral but the shifter felt like it required a shade more effort or attention that a Nipponese competitor. This also could have just been because I couldn’t adjust the shifter to my preference due to having to share the bike with other test riders.

A vibration through the low bars was present but it was never too intrusive.

Stainless lines are the stock fitment with the Brembo calipers grabbing dual 320s.

The Brembo calipers are plumbed with braided steel lines to a Nissin master cylinder. The brakes delivered race ready performance and, like a lot of race brake systems, had a little temperature related pump. The lever position which felt too close in the pits would move out a noticeable amount once I took to the track.

This got me reaching for a non-existent remote adjuster on the left handlebar but the very fact that I was absentmindedly dropping into racing habits shows how close this bike is to a race platform.

The dashboard control modes allow for throttle sensitivity (normal, rain, sport), max engine torque (sport, rain), engine braking (sport, normal). engine response (fast, slow), rpm limiter (sport, normal). There is no slipper clutch; the back torque is limited by ECU-controlled idle adjustments.

The bike does not have a slipper clutch and, instead, relies on the ECU to raise the idle speed when entering turns to prevent rear wheel chatter. It works very well and, of course, eliminates the excessive wear of clutch components that are part of the Faustian bargain with mechanical slipper clutches.

The Engine Control Unit is very trick. It was designed by some Magnetti Marelli alumni at ELDOR in Como, Italy. They do a lot of work for Audi, Ferrari and Lamborghini.

The ECU was designed with MV Agusta and MV has a three-year deal on exclusivity for the unit. The unit can drive 4 cylinders, 8 injectors, 4 ignition drives, a variable intake actuator, 2 lambda sensors as well as air flow estimation, speed density, dual linear injector models, lambda fuel management, full torque based management. It can detect ionization around the spark plug and reduce advance to prevent detonation.

It has total redundancy with dual micro architecture with diagnostics for each I/O. If it has a problem its failure mode keeps full power on the good circuitry, ; if it has a second failure it drops into limp home mode. One of the three bikes did experience a problem with the electric throttle but it only threw a code, it didn’t ever exhibit running problems.

After two sessions of getting to know the track we flipped the engine mode to Sport. In Sport mode the throttle butterflies open more rapidly, the redline moves up from a soft 500 RPM deceleration to a hard limit at the mechanical redline, and the engine braking tightens up a bit.

In this light it almost looks like it is in race primer.

Sport mode clearly illustrates how much of the motor’s rambunctious character is neutered by the Normal mode. Putting this in context, Normal mode does not punish indecisive throttle input. For street riding (like over bumps) or learning a new track the Normal mode smoothes out some of the rider’s or terrain’s rough inputs.

Sport mode requires, and rewards, conviction. If you are only going to open the throttle once coming out of a turn the bike responds immediately to the request. The available torque of the engine and its smooth transition to top end horsepower even offers the option of lugging through a sweeper a bit in third or screaming it in second. Either approach yielded the same ultimate speed, but that sort of flexibility can offer a lot of options for approaching a track.

We used to build our Army Of Darkness superbike GSX-R engines stroked out from 600 to 650. They had about the same bhp as a normal race prepped 600 but 20% more torque. This MV engine reminded me a lot of those championship winning superbike engines.

Although the F3 comes stock with eight way adjustable crank speed differential traction control (think Bazazz) I never took it off it lowest setting as the Dunlop rear only slid at the very end of the day. The stock traction control is all most track riders will ever need.

However, if you build up the motor past 140bhp you can buy an optional module that adds accelerometers and lean angle detection to the CAN bus data and the stock ECU will incorporate that additional information into its traction control algorithms. This capacity is clearly aimed at future World Supersport racers.

Eraldo Ferracci added a bit of preload to the rear spring, softened the fork preload a bit and tried to get the damping to match. These adjustments made the bike carve better (ie, raising the back, lowering the front) but I think my lingering discomfort with the front end was due to the stiff fork springs (.95) and relatively conservative rake number of 23.6. I also over heard one of the MV guys mentioning to another one that the Dunlops made the bike steer slower than the Pirellis.

It is entirely possible that the geometry of the MV was being compromised to some degree by tire dimensional changes.

According to Eraldo, the stock exhaust can be ditched along with its noise canceling power valve for an additional 6hp. You donna even hava to mess with the fuel.

One interesting characteristic of the bike was its ability to switch directions through the esses with ease. It is impossible to isolate the light weight (plastic gas tank), geometry and all the other host of characteristic that go into bike handling but another lurking secret about motorbike handling is the affect of the spinning crankshaft. Gyroscopes counter steering input with a 90-degree reaction and a lighter crank means less gyro and easier steering.

The effect is noticeable to the point that a Kawasaki 636, with its ever so slightly heavier crankshaft, steers slower than its 600cc counterpart.

A conventional inline bike has the wheels and crankshaft all spinning in the same direction. The F3 spins the crankshaft backwards (a la Yamaha’s GP bike) and uses the required-for-a-triple, yet much smaller, counter balancer shaft to reverse the direction of power transfer. With the crank spinning backwards its gyro is off setting, to some unknown degree, the gyro of the wheels, brake rotors and tires.

The effect would change based on both ground speed and engine speed but in the third gear high RPM hard right hard left hard right exit onto the front straight I though I was going to hit the inside curbs since my steering inputs were excessive compared to the reaction of the bike. I think the science was working.***

As luck would have it Brian Gillen (my luck not his) ended up sitting next to me at breakfast. Brian is an American from blue collar Buffalo New York who has lived in Italy for the last twelve years. He is also the Platform Manager for MV and currently lives in Bologna, Italy with his indigenous wife and kids.

Hey Brian, why is your engine so noisy and rattley?

And good morning to you too Sam. For your information most of the noise you are hearing is the transmission gears. Expensive gears like in the F4 are ground and hobbed. Those expensive ground gears can be made with a closer tolerance. The F3 transmission gears are shaved, which gives a tad more clearance but we had to make some concessions to price point on this bike and the thing we compromised on was some gear noise at idle.

I didn’t want to put rubber dampers in the cover to quiet it down because I didn’t want to compromise on weight. and then he reached for his plate of Danishes.

Why didn’t you just cheap out all the way and use the ones the Japanese use made of pressed powder so that the second gear rounds off in street applications and the 3-4 gear cluster can disintegrate in race applications? I asked before I realized that my question was my own answer as Brian simply raised an eyebrow at me over his coffee cup.

I hate working on engines at the track so I wanted the best hard parts we could put in the cases. But if you ever have a problem with it you can pull out the transmission cassette in about ten minutes.

But Brian, I pressed, intent on interrupting his breakfast, you put that cheap ass Nissin master cylinder up there on the handlebar for everyone to point at and laugh?

We couldn’t get a Brembo radial of comparable specification at this price point.

So, you are telling me, that you put in an expensive transmission that no one will ever see but everyone will hear, and you chose to save money on the glamour component that everyone can see?

I guess you could look at it that way

I let this sink in a minute. Here was an engineer, at an Italian company no less, focusing on quality metal, instead of exterior style.

So what other internal engine quality choices did you make that no one will ever be able to appreciate because of the future mechanical failures that won’t happen.

Brian looked at me carefully to see if I was kidding.

Cams driven from the end twist so that the cylinder at the other side of head can end up with cam timing as much as 8 degrees behind the cylinder closest to the cam gear. Most cams are cast, Ours are machined from billet and carbon nitrided to prevent that timing distortion. The crank is forged, not cast, and the whole thing is hardened, not just the bearing surfaces.

Even the counterbalance shaft is forged and nitrided.

I ran through the uncountable list of destroyed engines I have known and rejoined with: What about the valve components?

We are using Ti valves with forged collets. They are stamped and nitrided. The cam chain tensioner is from Japan but is it the same one we use on the F4 and it is very high quality.

GSX-R racers can buy similar parts from Yoshimura Suzuki to extend the life of their top end components but it is time consuming to install them. Brian is doing his customers a solid by installing high spec components from the factory.

This bike is not a cheap suit, it is a beautiful unique vehicle with serious performance built into it, all at a very competitive price point.

It would be understandable to buy one of these for the looks, but you don’t need to.

*Caveat Emptor – Let the Buyer Beware

**CAN bus is a data network used in motor vehicles. It is a bit more expensive than conventional wiring but it allows for more versatility and, more importantly, much lighter wiring harnesses because the ECU doesn’t need end runs to each sensor on the vehicle. It is cool.

*** Caveat, Kawasaki thought they were being really clever by halving the size of their alternator on their ZX-10 for a few years and driving it at twice engine speed. The resulting gyroscopic impacts played havoc with attempts to get the bike to handle.

Sidebar:

MV Agusta is basically the sole remaining creative two-wheeled vessel for Claudio Castiglioni. He and his brother (Giovanni) used to own Cagiva which got its start in the motorcycle industry by buying the old AMF- Harley Davidson plant in Varese. They then proceeded to buy up a number of moldering Italian brands which were well past their apogee including Ducati, Moto Morini, and Husqvarna.

They slowly sold off Ducati, Moto Morini and Husqvarna and then yo-yoed ownership of MV Agusta a number of times before its owner ship ended up back with Claudio Castiglioni. Now Cagiva is no more but MV Agusta lives on.

MV has a wholly owned subsidiary called CRC which handles all the design work. The design center is in San Marino (which is surrounded by Italy, but not in Italy) and houses 40 designers. MV has a separate design department for engines which has another 45 people.

That means that 40% of the MV staff are working on R D. That is an astronomically high number and shows a massive investment in the future. Assuming that they also require some warehouse guys and some administrative staff, it implies that they basically have as many people designing future motorcycles as building current ones.

The factory is in the far north of Italy in Varese. For those of you unfamiliar with Italy geography, this is like having your motorcycle factory in Lake Tahoe, or Vail.

Before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis all the MV Agustas were over €14,000. which, at that time, meant they cost over $20,000 or twice as much as a comparable Japanese bike.

Ironically, MV was owned by Harley Davidson in 2009. As Harley was being crushed by their leveraged customer base they scrambled for safety and shuttered Buell and sold off MV. Claudio picked it up in August of 2010. Harley was losing money hand over fist with the company.

They had total revenue of €35m with MV and their Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) was a stunning -€20m.

Castiglioni took over a sinking ship but with only a couple of quarters was able to stem the bleeding. He increased revenue to €43.5 m and reduced the EBITDA loss to -€-8.8m. 2011 was better with revenue of €44.7m and an EBITDA of -.5m. 2012 is shaping up to be their best year ever with a huge increase to 80m in revenue and an EBITDA profit of 5.7m.

That profit can be used for many purposes (like paying off operational debts incurred in 2010) or invested in more design and more production facilities. MV’s internal projections are for 2013 to be €13.6 (million?) in EBITDA profit on €101m in revenue. Those types of numbers indicate a strong and sustainable company.

The four cylinders are still intended to provide the halo product with the glamorous, but pricey, F4. The three cylinder bikes are designed to bring MV more into the meat of the mainstream motorcycle market with a more affordable price point. MV increased their model range from three bikes in 2010 to five in 2011. In 2012 they’ve got a total of eight, with three 675 models.

They sold a paltry 2213 bikes in 2009 but they are on track to sell 2,900 4-cylinder models in 2012 and a revenue fattening 5150 3- cylinder models in 2012. The goal is to have total sales of over 10,000 in 2013.

In bocca al lupo, MV.****

**** Italian idiomatic saying which is used to mean “good luck” but literally translates to: in the mouth of the wolf.

- MV Agusta F3 800: 146hp – 381 lbs – MVICS – EAS

- MV Agusta F4CC View BigbikeMotorCycles.com

- 2012 MV Agusta F3 675 motorcycle review @ Top Speed

- 2009 MV Agusta Brutale 1078RR – Teamspeed.com

- Bicycle