Suzuki GSX-R1100

Contents

Background [ edit ]

In the mid 1970s the motorcycle industry was in a period of transition. Because of noise and pollution, large two-strokes were being banned from the streets in many countries and there was no such thing as a true, four-stroke sport bike.

There were sporting four strokes, of course, but they were, for the most part, derivatives of regular motorcycles and those that came from Japan were, regardless of manufacturer, almost all the same. Built around an in-line four-cylinder air-cooled engine wrapped in a steel double cradle frame they were so similar, in fact, that they became known as the Universal Japanese Motorcycle (UJM).

Seeing the handwriting on the wall, Suzuki. which had made its reputation by building two strokes, built its first large four-stroke bikes, (see Suzuki GS series ) the DOHC GS750 and the GS400, for the American market in 1976. The GS550 arrived soon after and by 1978 the formidable GS1000 was making jaws drop in showrooms everywhere. 1980 saw the introduction of the 16-valve DOHC engine.

It also witnessed the creation of the then extremely radical influential Suzuki Katana. a bike which stylistically resembles a modern sportbike on the outside, but which was largely underpinned by existing technology of the day, although Suzuki were very quick to adopt the DOHC 16-valve cylinder head with their GSX 1100 range (including the Katana) in 1980.

In 1983 Honda introduced the VF750 Interceptor, (see Honda VF and VFR ) a radically innovative bike that set the trend for modern sportbikes. Kawasaki followed suit in 1984 with its Kawasaki GPZ900R Ninja .

Suzuki, meanwhile, soldiered on with its very powerful (a true 100bhp) and very torquey but heavy air-cooled 16-valve DOHC GS1100/GSX1100EZ/GSX1100EF/EG; a very capable machine but one definitely of its generation, even if it was at the forefront of it. This engine was typically enormously strong, many Suzuki engines get fully deserved ‘bulletproof’ reputations, as many drag racers found out – over 300BHP was perfectly possible and many ended up being turbocharged and tuned. The GSX750ES was well thought of too, especially for its fine handling, but again also was another machine that represented the most refined development of its own current generation.

At Suzuki it was felt that something much newer was needed for the future, both in chassis and engine terms.

By the mid-1980s the motorcycle industry was in a period of decline. Honda and Yamaha had engaged in a production war in order to decide who would become the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer and the result was oversupply. Brand new bikes went unsold and stacked up in warehouses and on dealers’ floors.

For many years after, consumers could buy new old stock bikes, a previous year’s model that had lain in its packing crate for years waiting to be sold, for the fraction of the price of a new bike. Needless to say, production tanked and manufacturers worried about their futures.

Development [ edit ]

In the midst of this market, Etsuo Yokouchi and his team of designers began work on a bike intended to change the market and outperform Honda’s Interceptor. They began in 1983 on Suzuki’s domestic market Gamma250 with the goal of producing a lightweight two-stroke for the streets. The RG250 was the world’s first production alloy framed motorcycle. Building upon the success of the Gamma, in 1984 they introduced the four-cylinder, four-stroke, aluminum framed GSXR400 for the Japanese market.

A full 18 percent lighter than comparable bikes on the market, the first GSXR set the tone for those that would follow.

I felt that if we could do a 400 cc bike that was 18 percent lighter, we should be able to do the same with a 750, recalls Mr. Yokouchi. [ 1 ] Using a current model GS/GSX750ES as a starting point, Yokouchi’s team went through every part, reducing weight wherever possible.

A new aluminum frame was engineered in a distinctive shape with square tubes stretching back over and around the top of the engine, then turning sharply downwards just past the carburetors to beneath the engine where they met the lower tubes. This design, unheard of at the time, would soon become familiar to a generation of motorcyclists and is often referred to as the “humpback” frame. Where welding would have added unnecessary weight aircraft quality rivets were used.

Weight was shaved back further and further until parts failed in the attempt to work out how much excess bulk could be trimmed away.

To save more weight, the suspension was engineered differently from most bikes of the day by mounting the top of the shock solidly to the frame while the bottom was attached to a banana shaped linkage that housed an excentric cam below the swing arm. The resulting system was lightweight, made suspension travel progressive and lowered the bike’s overall center of gravity.

While the engine used was a dual overhead cam. four valves per cylinder design typical of most bikes of the era it had unique features that set it apart from other air-cooled designs of the day. In the GSXR, oil would be used to cool parts of the engine, like the top of the combustion chamber, which were not typically well served by air cooling alone.

In order to provide enough oil for both cooling and lubrication, the team designed a double chamber pump, using the high-pressure side to lubricate the bearings while the low-pressure, high-volume side provided oil to the cooling circuit. The end result became known as the SACS – Suzuki Advanced Cooling System. The resulting motorcycle was rigorously tested to its breaking point, the weaknesses found and re-engineered until the bugs were worked out.

Many of the bike’s non mechanical design features were dictated by concerns other than pure mechanics. The flat front fascia and trade mark dual headlight were incorporated because designers wanted to give the bike the look of an endurance racer and because regulations dictated that the headlight be behind the front axle. The wide plastic panels under the seat were added to hide an unsightly exhaust hanger.

The resulting GSXR750 was introduced in 1985 but withheld from the United States due to tariff issues which would have imposed a 39.4 percent tax on each bike because it was over 700ccs. By waiting until 1986, Suzuki saved buyers money as the tax dropped to 24.4 percent. In the intervening year, Suzuki responded to European riders’ complaints about the bike’s stability by lengthening the swing arm by an inch.

With the ground work laid by earlier, smaller bikes, Suzuki introduced the GSXR1100 in 1986. The technology mirrored that of the GSXR750 but added big bore power, 137hp (102kW), to the mix while keeping the bike as light as possible, just 434 pounds.

Model history [ edit ]

As motorcycles have evolved, perspectives on the GSXR1100 have changed. When the bike was new, magazines lauded its power, handling and relative lack of weight. But today’s authors who compare it against 1994’s introduction of the Supersports bikes, driven by Tadao Baba ‘s development of the Honda Fireblade. [ 2 ] can use 20/20 hindsight to be more critical.

Recent articles, some with head to head comparisons with newer sportbikes, still rave about the powerful 1100cc engine but otherwise describe the GSXR1100 as large, heavy, and unstable. [ 3 ] Some of these assertions are borne out by Suzuki’s year-to-year tinkering with the frame geometry in order to make the bike handle better. The result is that different years have different handling characteristics on the road. Earlier bikes are lighter but the square-section alloy frame is prone to warping under extreme stress; later models are more rigid and offer increased power but suffer from increased weight.

The original bikes had square-section alloy frames, 18-inch wheels front and rear and a large endurance-style fairing. The early version of the engine was 1052cc in capacity and with greater similarity to the 750cc than later versions. The frame was somewhat stiffer than the frame on the 750—indeed the box section is noticeably thicker when compared side to side. Handling was secure, but not particularly fast.

The brakes consisted of two full floating discs at the front gripped by two sumitomo four-piston calipers and a small fixed disc gripped by a twin-piston caliper at the rear; Suzuki referred to this as the ‘Deca Piston’ set-up. Over the three years of production there were only minor changes, the largest being the switch to heavier three-spoke wheels on the last J model.

The 1989 (K model) fitted the 1100 engine (the first use of the now legendary [ citation needed ] and highly tunable and strong 1127cc oil-air-cooled design) into a new heavier, shorter and stiffer frame based on the previous year’s updated and extremely well received GSXR750J (the first of the ‘Slingshot bikes, named after the mix of flat-slide on one side and flat slide with a curve on the other Mukuni carbs). Magazine testers trying out the machines gave rave reviews but something was changed between then and the bikes going on sale. The ‘Slingshot’ 1100 K sold in the shops suffered handling problems, some [ who? ] claimed as a result of changed geometry, others [ who? ] said there was nothing wrong with the frame and that it was the suspension units that were set up all wrong.

Whatever it was, the standard bike was thought hard to handle and many modern magazines go so far as to advise buyers to avoid the K model, some even calling that year a “lemon”. [ 4 ] This was an attitude that was reinforced with the death of the Suzuki racer Phil Mellor at the Isle of Man in 1989 on the GSXR-1100K race bike. Jamie Whitham also crashed in the same race and it was enough to see the race authorities at the IOM ban the big bikes from racing for several years.

Suzuki GSX-R 1100 from 1992, last model with an oil-cooled engine

In 1990 the (L Model) bike was again tweaked and the wheelbase lengthened to correct the previous year’s handling problems. 1991 (M model) saw the addition of larger carburetors and major cosmetic changes when the fairing was reworked to place the headlights under a smooth plastic cover that helped the bike’s aerodynamics. 1992 (N model) was mechanically the same but offered more aggressive graphics in line with the time.

It was also the last year of the oil-cooled engines as the bike was re-designed for 1993.

1993 (WP model) saw major engine changes with the introduction of water cooling and some significant chassis changes. The move away from oil cooling allowed a surge in power, bringing total output to 155bhp at the crank and saw yet another hugely strong, reliable and extremely tunable Suzuki engine created ( Performance Bike in the UK reported on one taken to over 190bhp at the wheel – without the use of a turbo or nitrous oxide injection).

A new stiffer largely forged five-sided pentagonal cross-section frame was introduced along with an asymmetrical ‘banana’ swing-arm. Bigger Nissin six-piston brake calipers were fitted. The bike’s weight went up slightly as well, finally topping the 500-pound mark that Suzuki had been flirting with for years, but the overall look of the bike remained essentially the same as previous models.

1994 (WR model) saw nothing but colour changes.

Throughout the water-cooled years, 1993 to 1998, the GSXR’s design saw only one relatively major revision with the launch of the 1995 WS; everything else on the 1996 WT, 1997 WV and 1998 WW models was restricted to mere colour and graphics changes.

In keeping with the usual model development this followed many of the same changes introduced to previous year’s GSX-R750WR (also known as the SP). Minor but significant changes were made to the suspension (better quality 43mm USD forks replaced the 41mm USD forks used on the WP and WR models), the ignition and the cams (putting back the stack of bottom end and mid range pull many believed had gone AWOL with the WP and WR models).

The 1995 WS and onward models also featured a race-style braced swing-arm (in place of the asymmetrical ‘banana’ swing-arm found on the WP and WR models). Overall peak power (approx a measured 133bhp at the rear wheel – which made the then enormous factory claims of 155bhp, which many were sceptical of, at the crank perfectly credible) was unchanged but the torque curve on the bike was much improved. From the 1995 models weight fell back 221kg (487lbs) in the UK market. Some aerodynamic modifications were also introduced (most obviously narrowing the frontal area and reducing the size of the front fairing, the separate day time driving lamp disappeared and was incorporated into a new narrower twin headlamp cluster)

Many owners [ who? ] say these bikes are the easiest to live with and the most well rounded. Good fuel economy is even possible (over 45 mpg on a long cruising run * imp gallon)15,9 km/l and the slight changes made to the foot-peg position on the WS-on models even made distances a much less daunting prospect. In reality the bike had become a highly competent and monstrously fast (177mph was measured as the max speed of the standard WS bike by one UK bike magazine, Superbike in 1995) sports-touring machine, a far cry from its race-born origins.

It is clear [ according to whom? ] the design had reached its fullest form in the mid 1990s but that in terms of the leading edge of sports bike design it was already outdated and left behind as competition spurred the development of ever more powerful, ever lighter sport bikes.

This was demonstrated nowhere else more clearly than Suzuki’s own brand-new 1996 GSXR750WT, a return to the ultra-lightweight with a new beam frame, the SRAD design, which offered approx 115bhp at the rear wheel – coupled with the added boost from the new pressurised airbox design (always particularly efficient on Suzukis – Fast Bikes in the UK once measured a full 10bhp increase in power on the Crescent Racing shop’s dyno and wind tunnel @ 120mph in 2003 with a GSXR1000). All at a chassis weight ‘cost’ on the GSXR750WT of only 179 KG (394 LBs).

Clearly Suzuki were returning the GSXRs to their race-bred roots. Whilst Suzuki had clearly felt a great attachment to the cradle frame it is an interesting irony [ according to whom? ] that the Gsx-R250 and Gsxr400 used an alloy beam frame in the four model years 1986 – 1989 (inclusive).

1998 saw the last GSXR1100s roll off the assembly line and, despite how popular the bike had been in its heyday, there was no hue and cry as production quietly stopped. Suzuki would be without a big bore sportbike for three years before the GSXR1000 was released.

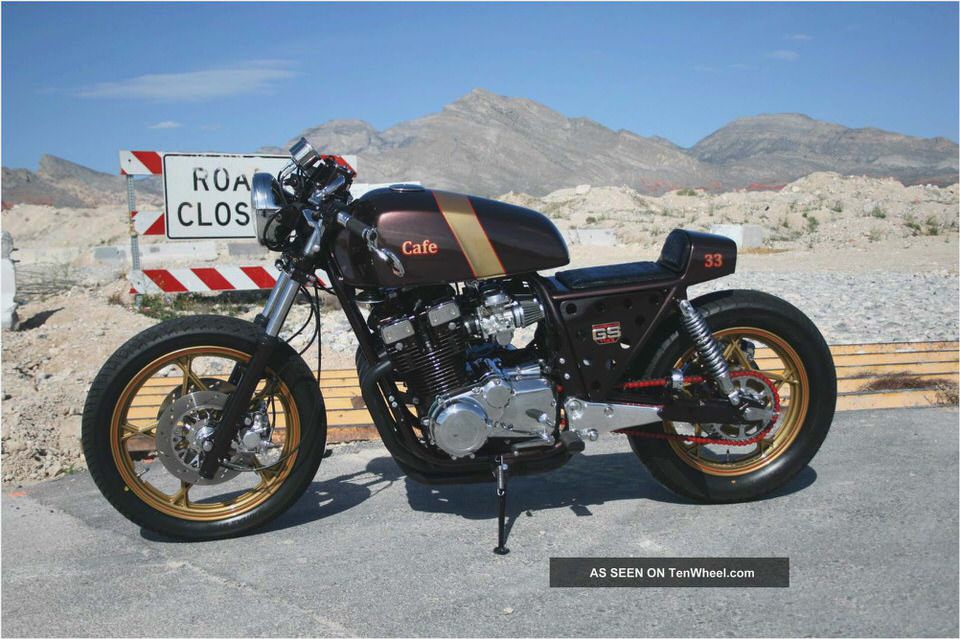

Despite the fact that over its production run tens of thousands of GSXR1100s were produced and sold all over the world, original examples in good condition have become something of a rarity. Many bikes were ridden hard and they were often crashed. As a result, they became and remain a popular starting point for street fighters and customs.

The bike is a tuner’s favorite – all versions respond well to tuning and even early models can make 140hp (104kW) at the wheel with relative ease. Simple intake modifications and a good exhaust will yield upwards of 10hp (7kW) increase. More enthusiastic tuning will see 160hp (119kW) or more, and many drag racers use superchargers or turbochargers with this engine to break the 500hp (370kW) mark. [ citation needed ]

A modified version of the original oil/air-cooled 1100 engine was used in the original 1157cc model of the Bandit 1200 motorcycle and taken to the biggest factory big-bore job in the hugely torque-laden GSX1400 up until 2008.

- 2007 Suzuki Boulevard M109r limited edition Suzuki Boulevard Motorcycle News

- The Suzuki DR-Z Repository – Mods for overlanding, and more!

- 2013 Suzuki Burgman 650 Executive ABS review – Road Tests: First Rides…

- Suzuki Gsr 600 Specs

- Suzuki VL 1500 K3 1500 LC Specs eHow