Obsolete Engines 101: The Mythical “V4″

The automobile as we know it (internal combustion, wheels, gears, etc.) has been around for a long time. 1672 is widely regarded as the beginning of the automobile, when Ferdinand Verbiest attached some wheels to a steam generator and created a vehicle that, by golly, moved itself. Most people point to Karl Benz as the father of the modern automobile, so that would pretty much mean it came into life with the granting of a patent in 1886.

In the ensuing 123 years, a lot of ideas and concepts that were deemed state-of-the-art, then normal, have long since come and gone. Some cars used to use leather as the friction surface on the clutch, because it was one of the grippiest, longest-lasting materials available at the time.

This means that the automobile has gone through a huge amount of evolution and reinvention as the years have gone by. It’s a pretty big market, with the average now at about 1 car per 11 people on earth, so the incentive to have an up-to-date product is pretty strong. Looking back at trends in the past show some interesting ideas that have sprouted and faded.

This is the first in a series of articles focusing on obsolete, outdated, or just plain unusual technology. Inspiration for this article goes to Michael Torbert. who brought up the question “has anyone ever made a V4?” Answer: Yes, they have.

The V4

When you talk to most car-ignorant people about cars, and ask them what kind of engine their Camry (or whatever) has, they’re liable to spout out something like “I think it’s got a V4?” Most of them don’t know exactly how uncommon a V4 really is, at least in automobile use. My research dug up three manufacturers of V4 engines for automobiles, and they’re all interesting.

Lancia was the first to debut a V4 in a production car, with the Lambda in 1922. It was an aluminum-block engine (very rare for the time) with pushrod actuation of the valvetrain. Displacement varied between 2.1 and 2.6L, with power outputs ranging from 49bhp to 69bhp, which were impressive outputs for the displacement at the time.

It was updated over the years and adapted to many different Lancias, including the Artena, Augusta, Aprilia, Ardea, and Appia. (What’s with Lancia and these A-names?) Power and sized ranged from a tiny 903cc and 28.8bhp up to the 55bhp 2.0L Artena.

The final application of the Lancia V4 was used in the gorgeous Fulvia, starting in 1963. The V4 was drastically redesigned for the Fulvia, with the block angle dropping from 20° in pre-war Lancias to about 12.5°. This allowed the use of a shared cylinder head (think Volkswagen VR6, then wonder where they got the idea) with two banks of cylinders.

Even cooler, it was a dual overhead cam V engine with only two camshafts – one operating the exhaust valves, one the intake.

The Fulvia’s V4 was available in a dizzying array of states of tune and displacement, ranging from a 1.1L 58bhp version – with low 7.8:1 compression ratio – up to the screaming 1.6L HF-tuned Series II motor, which cranked out 132bhp@6600rpm with an 11.3:1 compression ratio. The larger 1.6L V4 had it’s block angle dropped down to 11.2° for better balancing. Here are two good underhood shots of a series 1 Fulvia showing just how strange looking this engine really was.

I guess changing the spark plugs on this engine wouldn’t be all that difficult, would it?

Sadly, the Lancia V4 died with the Fulvia in 1976, replaced with a more conventional (and much cheaper to produce) inline-four cylinder engine. The influence of Fiat, which purchased Lancia in 1969, can be seen in the mass-market dumbing down of Lancia with the death of the V4. But Lancia wasn’t the only company with the idea that a V4 might be a good thing.

Ford dabbled with the V4 as well, and the story of the Euro Ford V4 is an interesting one too.

Ford of Europe actually had two different versions of the V4, one designed and produced by Ford of Germany (called the Taunus V4, it later evolved into the 6-cylinder Cologne series of motors) and one by Ford of England, the Essex V4 – which was named after the plant it was made in, respectively.

Both V4′s featured a counter-rotating balance shaft to neutralize harmonic vibrations inherent in a four-cylinder, an exacerbated by the V formation. Since one cylinder in a typical crankshaft I/C engine fires every 180°, this means there is no firing overlap with a four cylinder to cancel out the vibrations caused by the starting and stopping of the pistons.

Engines with 5 cylinders and up have overlap and are naturally smoother, although as I’ll discuss soon, the five-cylinder has it’s own balance problems. Even with the balance shaft, the V4′s were pretty rough little engines, and thanks to their 60° cylinder bank, not as high-revving as the single-head Lancia V4.

The German (Taunus) V4 came in varying displacements, including a 1.2, 1.3, 1.5 and later an enlarged and redesigned 1.7L unit. The 1.2L unit made 40bhp; the 1.7L cranked out 65. The Essex V4 was larger, at 1.7L or 2.0L, but didn’t really produce much more power than the German unit.

What’s odd about the Ford V4 was that they licensed it out to Saab. During the mid-sixties, Saab was looking to replace their three-cylinder two-stroke motors which were losing favor with the mass motoring public – I mean who wants to add in a certain amount of oil at every stop for gas? – and they had no chance of meeting upcoming emissions regulations. They chose the Ford V4 because it fit in the tiny engine bay of the 95 and 96, although they actually considered licensing the Lancia V4 as well.

The Ford V4-powered Saabs were a big hit with Saab nuts. While they offered only slight more power than the old 841cc two-stroke (55bhp vs. 40, or 57 in the GT/Monte Carlo with the sweet triple carb setup), the V4 had much more low-end torque, and was simpler and more reliable.

Being a Saab, they had all sorts of weird characteristics – like the siamesed exhaust ports and gear-driven cams.

The V4 could be found under the hood of the Saab Sonnett II V4 and Sonnett III as well, as seen in competition-spec in this picture:

It saw duty under the hood of German Fords like the Taunus and Capri, and later in enlarged 1.7L with the Granada, Consul, and Transit. Oh, and the Matra 530. Of course.

The Essex engine was much less interesting, and was much more short-lived. It’s important to notice that both Ford of Germany and England adapted the engines to V6 layouts, as people weren’t really fond of the naturally rough characteristics of the V4. No one really bothered to tune the motor besides Saab, who used it to power the 96 to many rally successes. Works-spec 96′s had bored-out 1933cc V4′s that made a healthy 150bhp; turbocharged ones pushed north of 200bhp.

Saab held onto the V4 the longest, with the last 96 V4 rolling off the line for European consumption in 1980. It was replaced by the 900, which used a Triumph-derived inline four that was canted 45° to the right for hood clearance..

The Ford V4′s still see use today, mostly in industrial equipment – like pumps and power generators. In the ford lineup, it was replaced by the overhead-cam “Pinto” inline four, which is still being produced in some forms today.

The final manufacturer of V4 powered automobiles is, I’ll admit, quite a bit weirder. ZAZ (Zaporizhia) was Ukraine’s main automotive manufacturer during the Soviet era, starting in 1960. Their most well known product is called the Zaporozhets, which is the communist-era equivalent of the VW Beetle.

Putin seems to like his, so you know it’s gotta be pretty awesome.

The Zaporozhets were assembled in the ZAZ factory, but the engines were designed, built, and shipped over for installation by MeMZ (Melitopol Engine Plant). They were similar in design to the VW flat-four, but had the cylinder banks at a 90° angle for ease of servicing – you can do more without dropping the engine out of the car, obviously.

All the MeMZ engines for the ZAZ cars were pushrod design (cam in block, overhead valves) with iron blocks, and seperate pressed-in steel liners. Much like the VW, they used a large fan driven off the crank pulley to cool the engine, as well as some adorable “ears” on the rear of the car to direct air into the engine bay.

Early ZAZ motors were either 746 or 887cc, with either 23 or 27 horsepower. When the second-generation ZAZ’s debuted (looking like an NSU Prinz rather than a Fiat 600) it had a larger 1.2L MeMZ V4, still air cooled, but producing 42bhp. How much does this look like a Corvair?

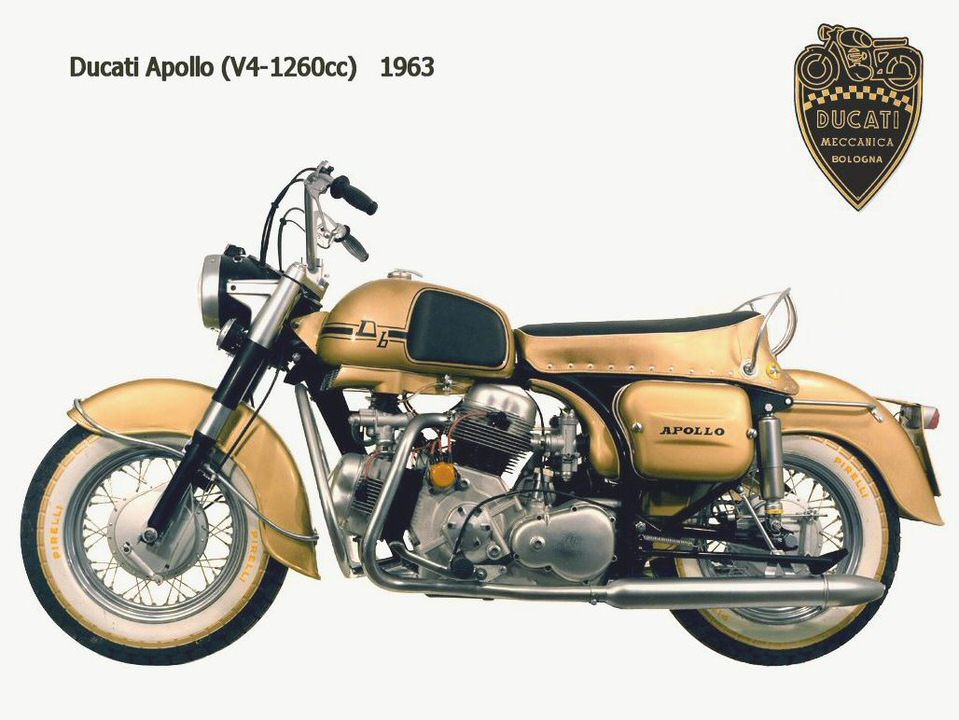

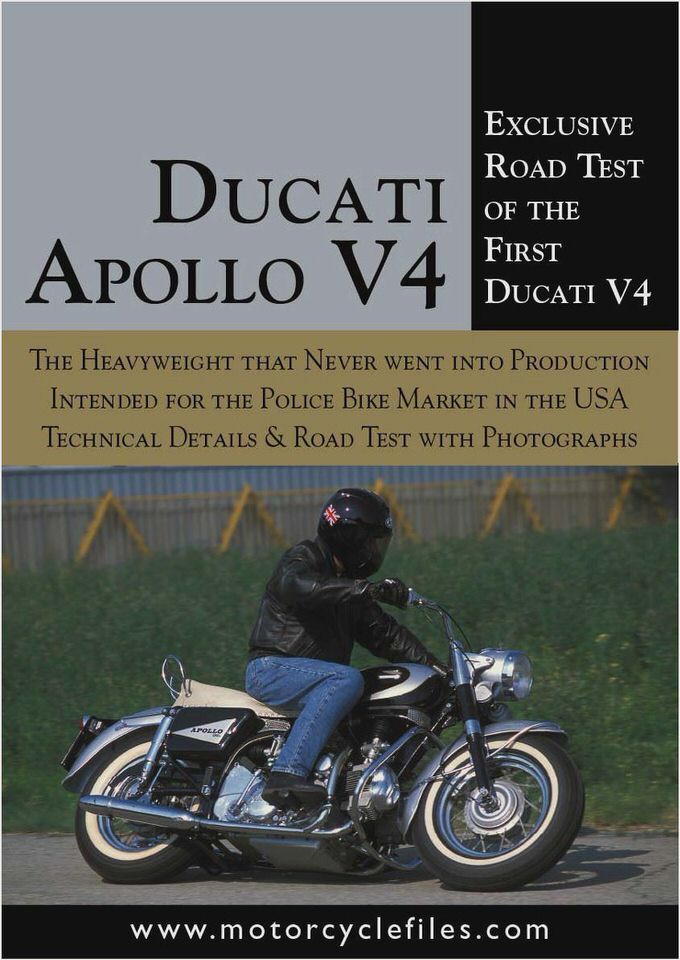

So the V4 wasn’t really all that popular in automotive use, but that wasn’t the case in other fields. Here’s a (partial) list of motorcycles that use V4 powerplants: Ducati Desmosedici, Yamaha V-Max, Honda RC212, Honda VF/VFR, Aprilia RSV4… you get the point. The compact and “square” dimensions of a V4 make a lot more sense when mounted in a motorcycle chassis where space is obviously at a premium.

The Yamaha VMax has been in production since 1985, virtually unchanged from the basic formula (cruiser chassis, muscular tire-burning V4, not that complicated) until a complete redesign last year.

The new V4 engine, pictured above, is an absolute monster. It displaces 1,679cc and is a dual-overhead-cam 4 valve design. Power output is 197bhp@9,000rpm and 123lb-ft@6,500rpm… which would be very good numbers for a car . much less a two-wheeled contraption.

The V4 is dead, long live the V4!

- Ducati Multistrada – Road Test & Review – Motorcyclist Online

- The Troy Bayliss Edition Ducati 1098R Review

- 2004 Ducati Monster M1000 Road Test Rider Magazine

- World’s First Ride: 2014 Ducati 899 Panigale Review Ducati Motor Cycles…

- 2009 Ducati 1198 S – Used 2009 1198 S at Motorcyclist Magazine