Blind Ambition: Everett Brashear, American Racing Legend Winner of 15 AMA nationals on Harley-Davidson and BSA flat-trackers.

Photographer. Everett Brashear Archives

If you ask Everett Brashear, crashing was more of a “when” than an “if.” He “finally got it” at a half-mile track in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1954. “I fell off in practice,” recalled Brashear, “and another guy ran right over the top of me. He hit me in the side of the head and severed the optic nerve, blinding me in the left eye. I was in the hospital for about a month and a half. I’d pretty much done it; my arm, leg, everything was busted up.”

Born in 1927, Brashear didn’t grow up riding motorcycles. His life of adventure began on a five-day journey in a converted cattle car from Houston, Texas, to San Diego, California, where he reported for boot camp during World War II. “I got assigned to a minesweeper and spent 19 months at sea,” he said. “On Tinian, we’d run ‘ping’ lines around the island [looking for submarines] and pick up B-29 crews that hit the water.”

After the war, Brashear returned to his hometown of Beaumont, Texas, but he didn’t begin racing until 1948 due to post-war shortages. “You couldn’t buy a motorcycle,” he said. Eventually, a local Indian dealer loaned Brashear a bike. But in his third race, he crashed and hurt his shoulder.

In 1950, he finally earned enough points to move up from Novice to Amateur.

“I ran that 45 Scout flathead on the Class C AMA Amateur circuit and transferred to Expert in 1951,” he said. “We had half-mile tracks all over Texas. The whole Southeast was a circuit for dirt-track guys. Class C was the same nationwide, and traveling all over was pretty tough. We’d team up and split the expenses.”

Competition was stiff, too. Others running Indians at the time were some of the top racers: Bobby Hill, Bill Tuman and Ernie Beckman, collectively known as “The Indian Wrecking Crew.”

“The Indians were the faster bike in those days, back when Floyd Emde won Daytona,” said Brashear. “Hill built the fastest Indians I ever ran against.”

With Indian already in financial trouble, Brashear began looking for something different. “A friend of mine found a 1941 WR,” he recalled, “a pretty fast bike that Harley built for Class C. The only ‘overheads’ were normally the foreign bikes. You could run a 30-cubic inch [500cc] overhead valve against the 45-inch [750cc] flathead. In 1951, I was winning a lot of races as an Expert and was getting to be the hot guy. The Harley-Davidson factory was helping me out a lot with parts and pieces.”

After recovering from injury, Brashear won five AMA nationals during the ’55 season, including a five-miler in Richmond, Virginia.

Brashear won his first national at Sturgis, South Dakota, in 1952 on Harley’s new foot-shift four-speed KR (the WR was hand-shift). What made the KR better than the WR? “Nothin’,” said Brashear. “It was a piece of junk, didn’t handle and the frame geometry was worse. But the factory thought I ought to have one.

I went to work modifying the frame—rake and trail, rear section—but didn’t get it handling until the end of the season.

“Winning Sturgis on the KR made me look good to Harley, and they started working full-time with me. By the end of the season, the bike worked really good at the mile at DuQuoin, and I won on the mile-and-a-half at Memphis, Tennessee—the only mile-and-a-half we ran on.” Long ovals were seeing speeds reminiscent of the board tracks of the 1920s. Memphis was banked, to boot, “and so fast,” said Brashear, “that I didn’t have the sprockets to gear it high enough.”

Brashear recalled a 200-miler at Dodge City in 1953: “They started the race in 116-degree heat. I tucked the front wheel in Turn 2, got off hard at about 100 mph and I ended up against a barbed-wire fence. A buddy of mine ran across the infield and asked if I was hurt.

I told him, ‘I don’t think so.’ When we got back to the hotel, I laid down and passed out from a concussion, so they just went to dinner without me.

“Bill Tuman won on a Norton Manx, but it was a sad day. Billy Huber passed out and crashed; he had a broken leg, and they thought he just had a concussion. He ended up dying of heat prostration.

One hundred and sixteen degrees, man, that will fry your brains. Billy was a neat little guy, a winner at Langhorne twice, same as me.”

Brashear won four nationals in 1953 and went into the ’54 season—the first year for the AMA Grand National Championship—with high expectations. But in May, his title hopes were crushed by the crash in Alabama that left him fighting for his life. Incredibly, less than four months later, Brashear won the mile at Langhorne.

Brashear’s on-track successes put him on the covers of popular national magazines, including Cycle.

How did Brashear compensate for the loss of his left eye? “I didn’t tell anybody about it,” he said. “All the AMA did was make you take a physical; there wasn’t an eye test or nothin’. The first race I tried to ride was in August at Springfield, where I won the consolation heat.”

Brashear won five nationals—half-miles at Richmond and Columbus and miles at DuQuoin, San Mateo and Springfield—in 1955 but finished a distant second in the championship to Brad Andres, who had won three of the four roadraces. Brashear scored victories at Columbus and Springfield in ’56 but slipped to fourth overall behind Joe Leonard, Andres and Al Gunter in the championship. The following year, 1957, was a turning point for Brashear.

“Walter Davidson was a big part of my success,” said Brashear, “along with Hank Syvertsen, who had been in the race department for 30-something years. I was doing R-D stuff when I wasn’t racing, and Walter wanted me to take over the race department. But my wife wasn’t going to leave our home, as we had a daughter and I was gone all the time. I told Walter no, and he hired Dick O’Brien.

Hank came in one day asking what was going on, and they told him they’d retired him, and, well, he was mad.

“O’Brien and I would talk on the phone every day. One day, Dick called me and said he came to work and everything was gone but his desk. That weekend, Hank had rented a U-Haul. He went in and cleaned out 44 years of records, everything from all the chief engineers, all the way back to the board-track days—took it all and put it in his garage.

As far as I know, they never got the records back. It hurt him. He was part of the family, and he’d been put out to pasture.”

Despite Brashear’s good standing within Harley-Davidson, his relationship with The Motor Company was about to end, as well. In 1957, in every race in which Brashear competed, something went wrong.

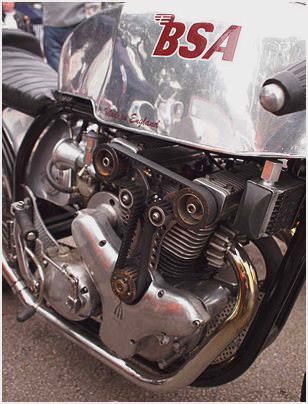

“I won a lot of races, but I didn’t win any nationals. I had gotten so sick and tired of this, so I went to the BSA dealer in Dayton, Ohio, who used to put Dick Mann and me up at his house. I asked him if he still had that old Gold Star and if he’d mind if I rode it.

I went out and won two races that next weekend. I told him, ‘I’m going to get in trouble with Harley about this.’”

After losing his Harley ride at the end of the 1957 season, Brashear raced a BSA tuned by legendary engine-builder Tom Sifton. In July, he famously won the San Jose Mile, nipping Sammy Tanner and Carroll Resweber at the line.

Sure enough, word soon arrived that Davidson had fired Brashear and sold his loaner streetbike. “I called him for two or three days,” said Brashear, “but he wouldn’t talk to me, so I went and signed up with BSA for 1958. Old man [Tom] Sifton built a fantastic 500cc Single. It only won one national, but it should have won all of them.

Sifton taught me more about building racing machines than anyone. We could get three or four more horses than the factory.”

Brashear’s last national win came at the 1960 Sacramento Mile on a Harley-Davidson. He later did some roadracing, finishing sixth in the 1964 Daytona 200 on Dick Mann’s G50 Matchless. “I had a good chance in race cars in NASCAR,” said Brashear. “One year at Daytona, Lee Petty tore my car in half when he hit me. Joe Leonard was going to try and get me an Indy ride, but you’ve got to have two eyes to run Indianapolis.”

Brashear eventually accepted a management position with Triumph. “I used to do a lot of riding with Keenan Wynn and Lee Marvin. Marvin was a fantastic athlete; people just don’t realize what an athlete that guy was.” Brashear left Triumph for the lure of the Japanese manufacturers, starting with Yamaha. “I was with them from 1968, district manager in the West.” Brashear then spent 1971 as sales manager for Kawasaki.

At the end of ’71, Edison Dye hired Brashear at Husqvarna. “My corporation was Husqvarna West—everything west of the Mississippi,” he said. “They sent former world champion Rolf Tibblin to help start the Husqvarna MX school at Carlsbad Raceway.

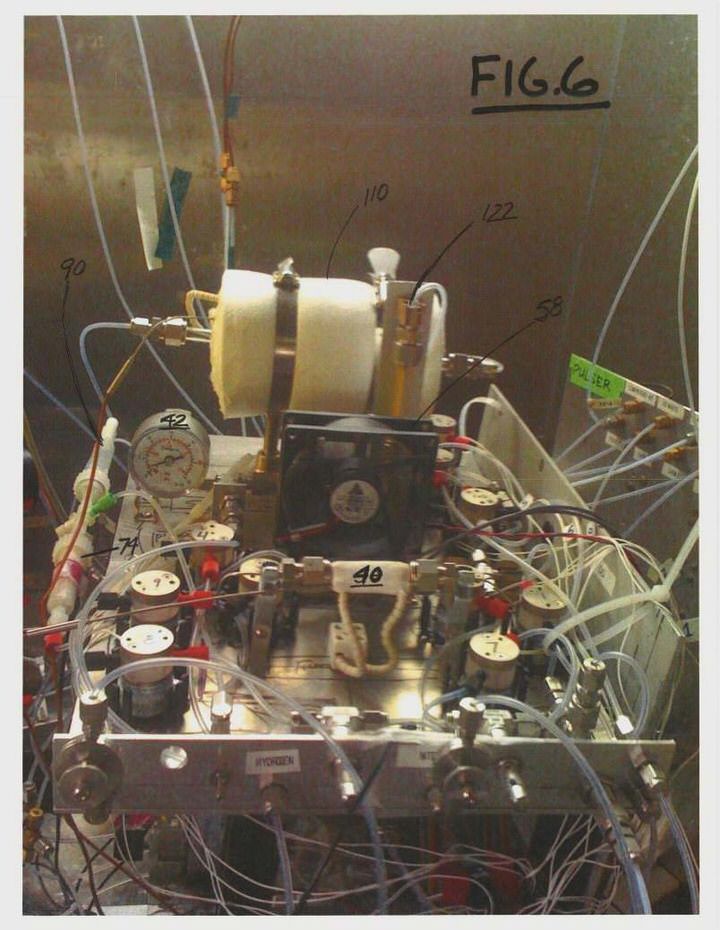

After retiring from racing, Brashear donned a suit and moved to the corporate side of the motorcycle industry. Here, Brashear (left) and off-road champion Malcolm Smith inspect a prototype two-stroke roadracer in the Husqvarna R-D department.

“Rolf might be the strongest man I’ve ever met in my life. He was unbelievable. I’d ridden up to Rolf’s house on an old Knucklehead.

We were drinking schnapps, and Rolf said, ‘You’re not riding home.’ I said, ‘I’m riding this bike home tonight.’ Rolf said, ‘ This is why you aren’t riding home tonight!’ He picked up that whole Harley, all 600 pounds of it, and set it on his trailer all by himself. I told him, ‘You’re right.’”

Tibblin wasn’t the only legend at Husqvarna. “Mark Blackwell, our 500cc national champion, and I were really close,” said Brashear. “Malcolm Smith was one hell of a racer. J.N. Roberts was on a whole other level.”

But Brashear claims the Swedes didn’t like the motorcycle business. “Brad Lackey wasn’t winning because Husqvarna wasn’t keeping up with the technology,” he said. “Their biggest dollar volume was chainsaws, appliances and sewing machines.”

So, when Husqvarna wanted to move its sales office to Tennessee, what did Brashear tell them? “Find somebody else.”

After leaving Husqvarna West, Brashear worked for various motor-cycle-related companies until his retirement in 1996. He was inducted into the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 1998.

Asked if he’d recommend a career in racing, Brashear, now 85, replied, “Lloyd Ruby and I started racing the same year in Texas. He was an absolutely fantastic race-car driver; he should have won Indy five times. One day, Lloyd asked my son, an F-15 Eagle pilot, if he was racing motorcycles. When he said no, Lloyd said, ‘Oh man, you don’t know what you’re missing.’ I started laughing and told Lloyd, ‘You know, we were the stupidest idiots in the world to do what we did.’”

First national win – 1952 Sturgis 5-mile – Everett Brashear poses on his 1952 Sturgis-national-winning Harley-Davidson. The victory was the fir’

1955 Harley-Davidson advertisement – After recovering from injury, Brashear won five AMA nationals during the 55 season, including a five’

Cycle cover – October 1960 – Brashears on-track successes put him on the covers of popular national magazines, including Cycle.’

- Rick Sieman: SuperHunky.com

- BSA 650cc Thunderbolt Review

- 1945 BSA B31. Rare Early Model The BSA & Military Bicycle Museum

- 1971 BSA Fury – Classic Motorcycle Review – RealClassic.co.uk

- Steves Home Page mainly on BSA Motorcycles